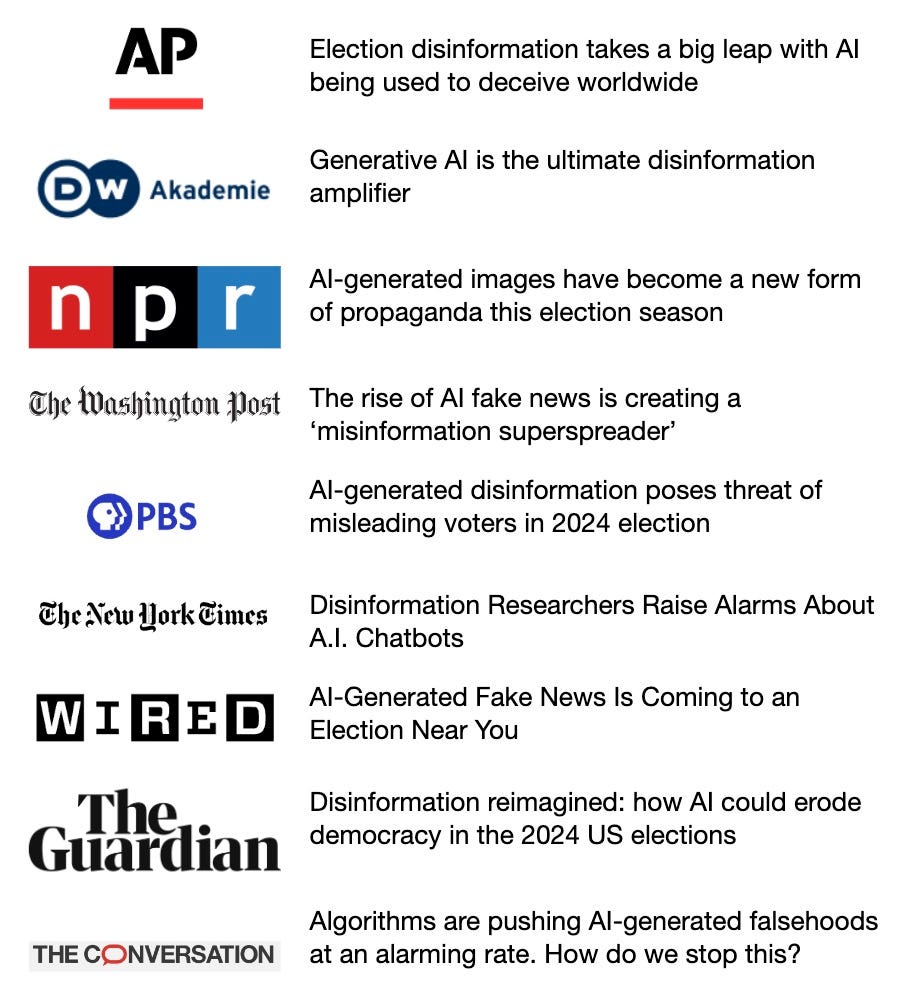

AI-generated misinformation was one of the top concerns during the 2024 U.S. presidential election. In January 2024, the World Economic Forum claimed that “misinformation and disinformation is the most severe short-term risk the world faces” and that “AI is amplifying manipulated and distorted information that could destabilize societies.” News headlines about elections in 2024 tell a similar story:

In contrast, in our past writing, we predicted that AI would not lead to a misinformation apocalypse. When Meta released its open-weight large language model (called LLaMA), we argued that it would not lead to a tidal wave of misinformation. And in a follow-up essay, we pointed out that the distribution of misinformation is the key bottleneck for influence operations, and while generative AI reduces the cost of creating misinformation, it does not reduce the cost of distributing it. A few other researchers have made similar arguments.

Which of these two perspectives better fits the facts?

Fortunately, we have the evidence of AI use in elections that took place around the globe in 2024 to help answer this question. Many news outlets and research projects have compiled known instances of AI-generated text and media and their impact. Instead of speculating about AI’s potential, we can look at its real-world impact to date.

We analyzed every instance of AI use in elections collected by the WIRED AI Elections Project, which tracked known uses of AI for creating political content during elections taking place in 2024 worldwide. In each case, we identified what AI was used for and estimated the cost of creating similar content without AI.

We find that (1) most AI use isn’t deceptive, (2) deceptive content produced using AI is nevertheless cheap to replicate without AI, and (3) focusing on the demand for misinformation rather than the supply is a much more effective way to diagnose problems and identify interventions.

To be clear, AI-generated synthetic content poses many real dangers: the creation of non-consensual images of people and child sexual abuse material and the enabling of the liar’s dividend, which allows those in power to brush away real but embarrassing or controversial media content about them as AI-generated. These are all important challenges. This essay is focused on a different problem: political misinformation.

Improving the information environment is a difficult and ongoing challenge. It’s understandable why people might think AI is making the problem worse: AI does make it possible to fabricate false content. But that has not fundamentally changed the landscape of political misinformation.

Paradoxically, the alarm about AI might be comforting because it positions concerns about the information environment as a discrete problem with a discrete solution. But fixes to the information environment depend on structural and institutional changes rather than on curbing AI-generated content.

We analyzed all 78 instances of AI use in the WIRED AI Elections Project (source for our analysis). We categorized each instance based on whether there was deceptive intent. For example, if AI was used to generate false media depicting a political candidate saying something they didn’t, we classified it as deceptive. On the other hand, if a chatbot gave an incorrect response to a genuine user query, a deepfake was created for parody or satire, or a candidate transparently used AI to improve their campaigning materials (such as by translating a speech into a language they don’t speak), we classify it as non-deceptive.

To our surprise, there was no deceptive intent in 39 of the 78 cases in the database.

The most common non-deceptive use of AI was for campaigning. When candidates or supporters used AI for campaigning, in most cases (19 out of 22), the apparent intent was to improve campaigning materials rather than mislead voters with false information.

We even found examples of deepfakes that we think helped improve the information environment. In Venezuela, journalists used AI avatars to avoid government retribution when covering news adversarial to the government. In the U.S., a local news organization from Arizona, Arizona Agenda, used deepfakes to educate viewers about how easy it is to manipulate videos. In California, a candidate with laryngitis lost his voice, so he transparently used AI voice cloning to read out typed messages in his voice during meet-and-greets with voters.

Reasonable people can disagree on whether using AI in campaigning materials is legitimate or what the appropriate guardrails need to be. But using AI for campaign materials in non-deceptive ways (for example, when AI is used as a tool to improve voter outreach) is much less problematic than deploying AI-generated fake news to sway voters.

Of course, not all non-deceptive AI-generated political content is benign. Chatbots often incorrectly answer election-related questions. Rather than deceptive intent, this results from the limitations of chatbots, such as hallucinations and lack of factuality. Unfortunately, these limitations are not made clear to users, leading to an overreliance on flawed large language models (LLMs).

For each of the 39 examples of deceptive intent, where AI use was intended to make viewers believe outright false information, we estimated the cost of creating similar content without AI—for example, by hiring Photoshop experts, video editors, or voice actors. In each case, the cost of creating similar content without AI was modest—no more than a few hundred dollars. (We even found that a video involving a hired stage actor was incorrectly marked as being AI-generated in WIRED’s election database.)

In fact, it has long been possible to create media with outright false information without using AI or other fancy tools. One video used stage actors to falsely claim that U.S. Vice President and Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris was involved in a hit-and-run incident. Another slowed down the vice president’s speech to make it sound like she was slurring her words. An edited video of Indian opposition candidate Rahul Gandhi showed him saying that the incumbent Narendra Modi would win the election. In the original video, Gandhi said his opponent would not win the election, but it was edited using jump cuts to take out the word “not.” Such media content has been called “cheap fakes” (as opposed to AI-generated “deepfakes”).

There were many instances of cheap fakes used in the 2024 U.S. election. The News Literacy Project documented known misinformation about the election and found that cheap fakes were used seven times more often than AI-generated content. Similarly, in other countries, cheap fakes were quite prevalent. An India-based fact checker reviewed an order of magnitude more cheap fakes and traditionally edited media compared to deepfakes. In Bangladesh, cheap fakes were over 20 times more prevalent than deepfakes.

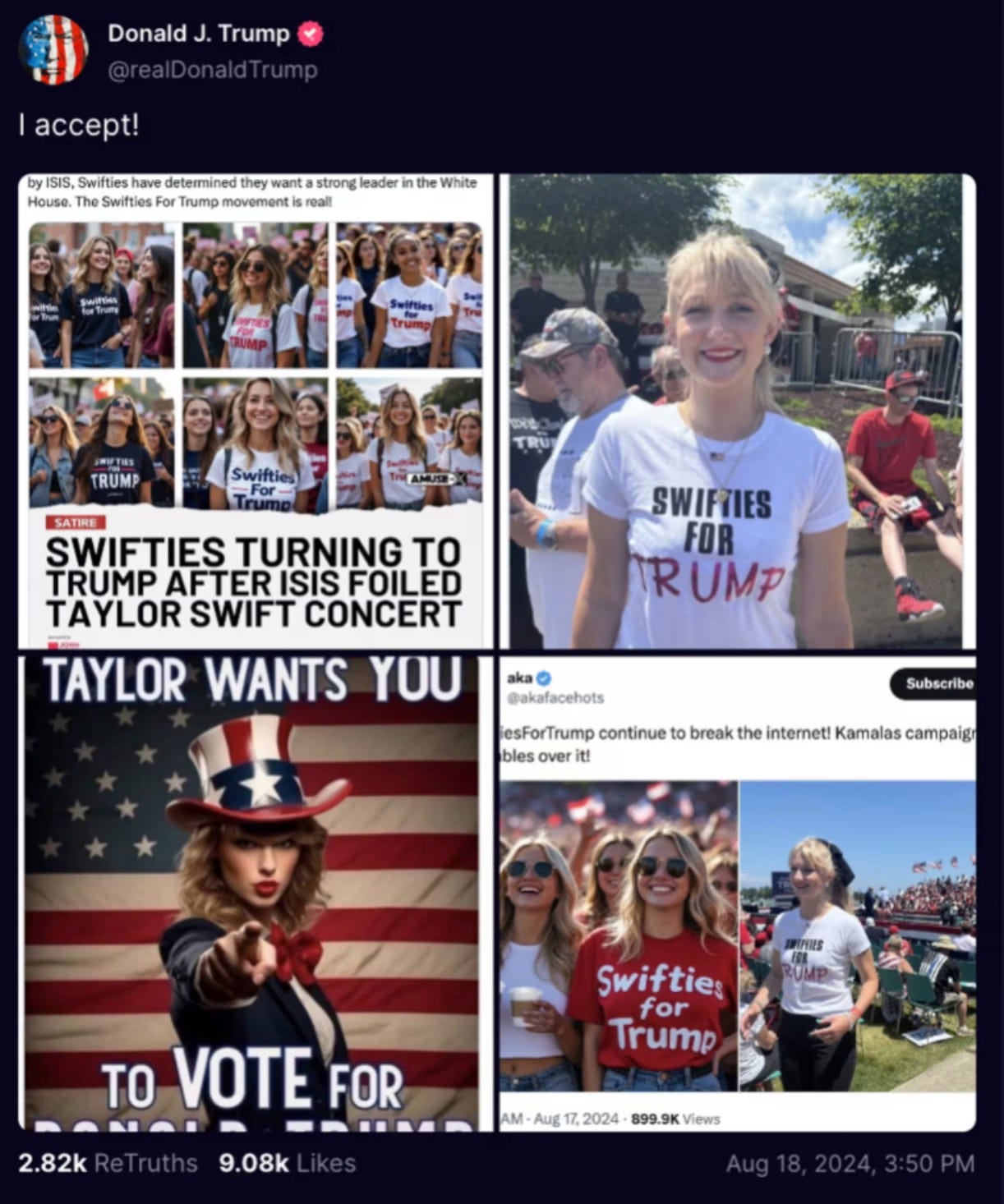

Let’s consider two examples to analyze how cheap fakes could have led to substantially similar effects as the deepfakes that got a lot of media attention: Donald Trump’s use of Taylor Swift deepfakes to campaign and a voice-cloned robocall that imitated U.S. President Joe Biden in the New Hampshire primary asking voters not to vote.

Trump’s use of Swift deepfakes implied that Taylor Swift had endorsed him and that Swift fans were attending his rallies en masse. In the wake of the post, many media outlets blamed AI for the spread of misinformation.

But recreating similar images without AI is easy. Images depicting Swift’s support could be created by photoshopping text endorsing Trump onto any of her existing images. Likewise, getting images of Trump supporters wearing “Swifties for Trump” t-shirts could be achieved by distributing free t-shirts at a rally—or even selectively reaching out to Swift fans at Trump rallies. In fact, two of the images Trump shared were real images of a Trump supporter who is also a Swift fan.

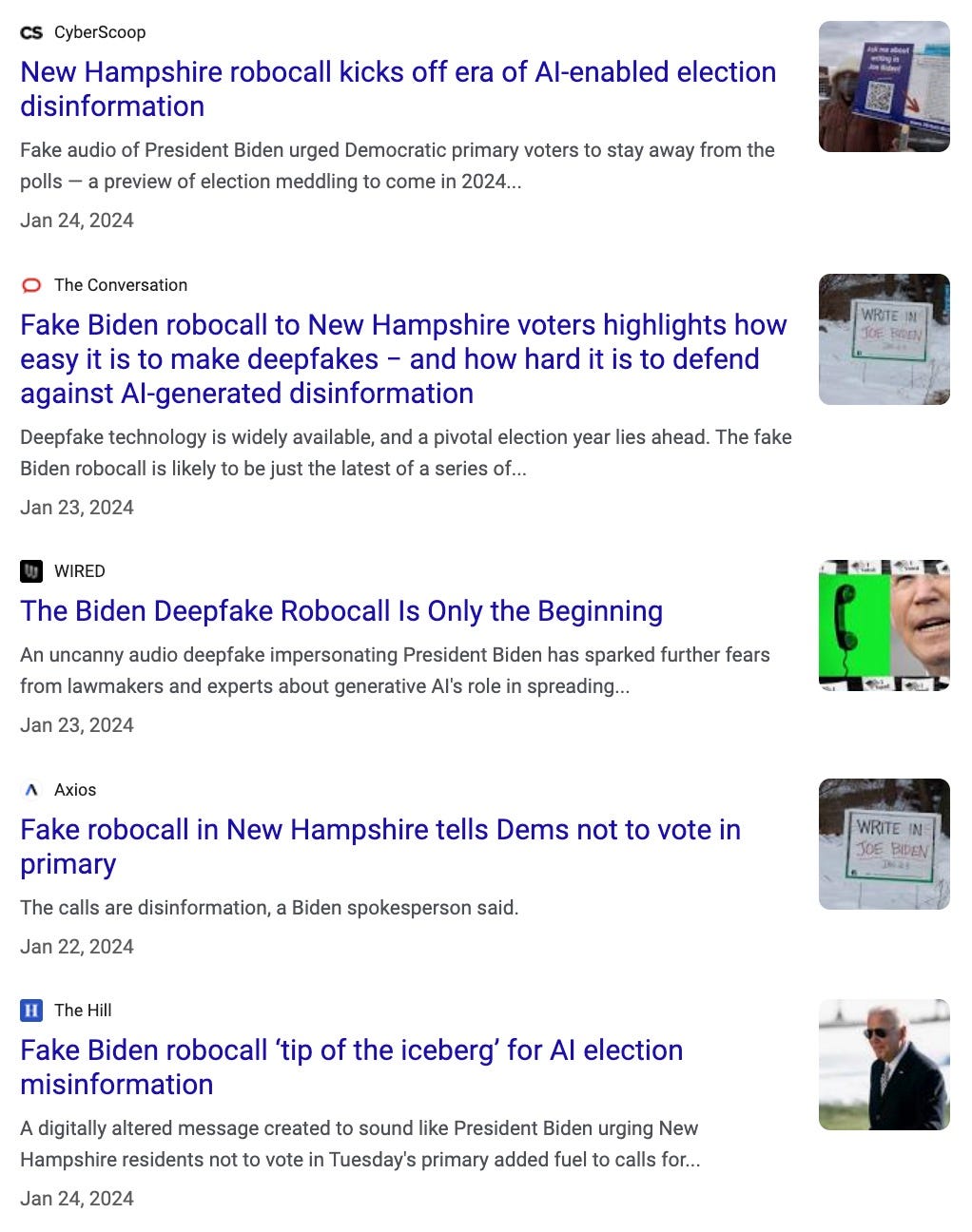

Another incident that led to a brief panic was an AI clone of President Joe Biden’s voice that asked people not to vote in the New Hampshire primary.

Rules against such robocalls have existed for years. In fact, the perpetrator of this particular robocall was fined $6 million by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). The FCC has tiplines to report similar attacks, and it enforces rules around robocalls frequently, regardless of whether AI is used. Since the robocall used a static recording, it could have been made about as easily without using AI—for instance, by hiring voice impersonators.

It is also unclear what impact the robocall had: The efficacy of the deepfake depends on the recipient believing that the president of the United States is personally calling them on the phone to ask them not to vote in a primary.

Is it just a matter of time until improvements in technology and the expertise of actors seeking to influence elections lead to more effective AI disinformation? We don’t think so. In the next section, we point out that structural reasons that drive the demand for misinformation are not aided by AI. We then look at the history of predictions about coming waves of AI disinformation that have accompanied the release of new tools—predictions that have not come to pass.

Misinformation can be seen through the forces of supply and demand. The supply comes from people who want to make a buck by generating clicks, partisans who want their side to win, or state actors who want to conduct influence operations. Interventions so far have almost entirely tried to curb the supply of misinformation while leaving the demand unchanged.

The focus on AI is the latest example of this trend. Since AI reduces the cost of generating misinformation to nearly zero, analysts who look at misinformation as a supply problem are very concerned. But analyzing the demand for misinformation can clarify how misinformation spreads and what interventions are likely to help.

Looking at the demand for misinformation tells us that as long as people have certain worldviews, they will seek out and find information consistent with those views. Depending on what someone’s worldview is, the information in question is often misinformation—or at least would be considered misinformation by those with differing worldviews.

In other words, successful misinformation operations target in-group members—people who already agree with the broad intent of the message. Such recipients may have lower skepticism for messages that conform to their worldviews and may even be willing to knowingly amplify false information. Sophisticated tools aren’t needed for misinformation to be effective in this context. On the flip side, it will be extremely hard to convince out-group members of false information that they don’t agree with, regardless of AI use.

Seen in this light, AI misinformation plays a very different role from its popular depiction of swaying voters in elections. Increasing the supply of misinformation does not meaningfully change the dynamics of the demand for misinformation since the increased supply is competing for the same eyeballs. Moreover, the increased supply of misinformation is likely to be consumed mainly by a small group of partisans who already agree with it and heavily consume misinformation rather than to convince a broader swath of the public.

This also explains why cheap fakes such as media from unrelated events, traditional video edits such as jump cuts, or even video game footage can be effective for propagating misinformation despite their low quality: It is much easier to convince someone of misinformation if they already agree with its message.

Our analysis of the demand for misinformation may be most applicable to countries with polarized close races where leading parties have similar capacities for voter outreach, so that voters’ (mis)information demands are already saturated.

Still, to our knowledge, in every country that held elections in 2024 so far, AI misinformation had much less impact than feared. In India, deepfakes were used for trolling more than spreading false information. In Indonesia, the impact of AI wasn’t to sow false information but rather to soften the image of then-candidate, now-President Prabowo Subianto (a former general accused of many past human rights abuses) using AI-generated digital cartoon avatars that depicted him as likable.

The 2024 election cycle wasn’t the first time when there was widespread fear that AI deepfakes would lead to rampant political misinformation. Strikingly similar concerns about AI were expressed before the 2020 U.S. election, though these concerns were not borne out. The release of new AI tools is often accompanied by worries that it will unleash new waves of misinformation:

-

2019. When OpenAI released its GPT-2 series of models in 2019, one of the main reasons it held back on releasing the model weights for the most capable models in the series was its alleged potential to generate misinformation.

-

2023. When Meta released the LLaMA model openly in 2023, multiple news outlets reported concerns that it would trigger a deluge of AI misinformation. These models were far more powerful than the GPT-2 models released by OpenAI in 2019. Yet, we have not seen evidence of large-scale voter persuasion attributed to using LLaMA or other large language models.

-

2024. Most recently, the widespread availability of AI image editing tools on smartphones has prompted similar concerns.

In fact, concerns about using new technology to create false information go back over a century. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the advent of technologies for photo retouching. This was accompanied by concerns that retouched photographs would be used to deceive people, and, in 1912, a bill was introduced in the U.S. that would have criminalized photo editing without subjects’ consent. (It died in the Senate.)

Thinking of political misinformation as a technological (or AI) problem is appealing because it makes the solution seem tractable. If only we could roll back harmful tech, we could drastically improve the information environment!

While the goal of improving the information environment is laudable, blaming technology is not a fix. Political polarization has led to greater mistrust of the media. People prefer sources that confirm their worldview and are less skeptical about content that fits their worldview. Another major factor is the drastic decline of journalism revenues in the last two decades—largely driven by the shift from traditional to social media and online advertising. But this is more a result of structural changes in how people seek out and consume information than the specific threat of misinformation shared online.

As history professor Sam Lebovic has pointed out, improving the information environment is inextricably linked to the larger project of shoring up democracy and its institutions. There’s no quick technical fix, or targeted regulation, that can “solve” our information problems. We should reject the simplistic temptation to blame AI for political misinformation and confront the gravity of the hard problem.

This essay is cross-posted to the Knight First Amendment Institute website. We are grateful to Katy Glenn Bass for her feedback.