The ability of LLMs to execute commands through plain language (e.g. English) has enabled agentic systems that can complete a user query by orchestrating the right set of tools (e.g. ToolFormer, Gorilla). This, along with the recent multi-modal efforts such as the GPT-4o or Gemini-1.5 model, has expanded the realm of possibilities with AI agents. While this is quite exciting, the large model size and computational requirements of these models often requires their inference to be performed on the cloud. This can create several challenges for their widespread adoption. First and foremost, uploading data such as video, audio, or text documents to a third party vendor on the cloud, can result in privacy issues. Second, this requires cloud/Wi-Fi connectivity which is not always possible. For instance, a robot deployed in the real world may not always have a stable connection. Besides that, latency could also be an issue as uploading large amounts of data to the cloud and waiting for the response could slow down response time, resulting in unacceptable time-to-solution. These challenges could be solved if we deploy the LLM models locally at the edge.

However, current LLMs like GPT-4o or Gemini-1.5 are too large for local deployment. One contributing factor is that a lot of the model size ends up memorizing general information about the world into its parametric memory which may not be necessary for a specialized downstream application. For instance, if you ask a general factual question from these models like a historical event or well-known figures, they can produce the results using their parametric memory, even without having additional context in their prompt. However, it seems like this implicit memorization of training data into the parametric memory is correlated with “emergent” phenomena in LLMs such as in-context learning and complex reasoning, which has been the driving force behind scaling the model size.

However, this leads to an intriguing research question:

Can a smaller language model with significantly less parametric memory emulate such emergent ability of these larger language models?

Achieving this would significantly reduce the computational footprint of agentic systems and thus enable efficient and privacy-preserving edge deployment. Our study demonstrates that this is feasible for small language models through training with specialized, high-quality data that does not require recalling generic world knowledge.

Such a system could particularly be useful for semantic systems where the AI agent’s role is to understand the user query in natural language and, instead of responding with a ChatGPT-type question answer response, orchestrate the right set of tools and APIs to accomplish the user’s command. For example, in a Siri-like application, a user may ask a language model to create a calendar invite with particular attendees. If a predefined script for creating calendar items already exists, the LLM simply needs to learn how to invoke this script with the correct input arguments (such as attendees’ email addresses, event title, and time). This process does not require recalling/memorization of world knowledge from sources like Wikipedia, but rather requires reasoning and learning to call the right functions and to correctly orchestrate them.

Our goal is to develop Small Language Models (SLM) that are capable of complex reasoning that could be deployed securely and privately at the edge. Here we will discuss the research directions that we are pursuing to that end. First, we discuss how we can enable small open-source models to perform accurate function calling, which is a key component of agentic systems. It turns out that off-the-shelf small models have very low function calling capabilities. We discuss how we address this by systematically curating high-quality data for function calling, using a specialized Mac assistant agent as our driving application. We then show that fine-tuning the model on this high quality curated dataset, can enable SLMs to even exceed GPT-4-Turbo’s function calling performance. We then show that this could be further improved and made efficient through a new Tool RAG method. Finally, we show how the final models could be deployed efficiently at the edge with real time responses.

[embedded content]

Demo of TinyAgent-1B along with Whisper-v3 running locally deployed locally on a Macbook M3 Pro. The framework is open sourced and available at https://github.com/SqueezeAILab/TinyAgent

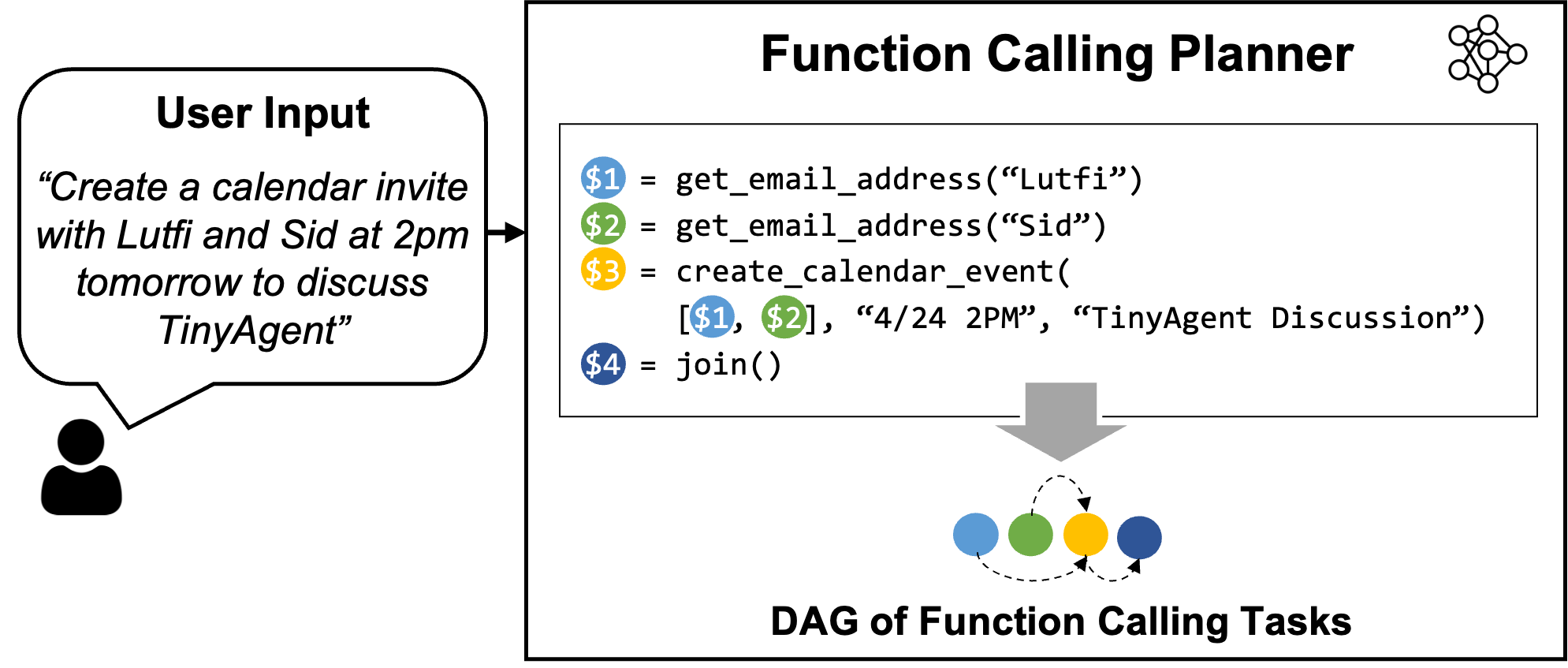

Figure 1: Overview of the LLMCompiler Function Calling Planner. The Planner understands the user query and generates a sequence of tasks with their inter-dependencies. These tasks are then dispatched by the LLMCompiler framework to accomplish the user command. In this example, Task $1 and $2 are fetched together to retrieve the email addresses of Sid and Lutfi independently. After each task is performed, the results are forwarded to Task $3 which creates the calendar event. Before executing Task $3, LLMCompiler replaces the placeholder variables (e.g., the variable $1 and $2 in Task $3) with actual values.

As mentioned above, our main interest is applications where the AI agent translates the user query into a sequence of function calls to complete the tasks. In such applications, the model doesn’t need to write the function definition itself since the functions (or APIs) are mostly pre-defined and already available. Therefore, what the model needs to do is to determine (i) which functions to call, (ii) the corresponding input arguments, and (iii) the right order of calling these functions (i.e. function orchestration) based on the required interdependency across the function calls.

The first question is to find an effective way to equip SLMs to perform function calling. Large models such as GPT-4 are able to perform function calling, but how can this be achieved with open source models? LLMCompiler is a recent framework from our group that enables this by instructing the LLM to output a function calling plan that includes the set of functions that it needs to call along with the input arguments and their dependencies (see the example in Figure 1). Once this function calling plan is generated, we can parse it and call each function based on the dependencies.

The critical part here is to teach the model to create this function calling plan with the right syntax and dependency. The original LLMCompiler paper only considered large models, such as LLaMA-2 70B, which have complex reasoning capabilities to create the plan when provided with sufficient instructions in their prompts. However, can smaller models be prompted the same way to output the correct function calling plan? Unfortunately, our experiments showed that off-the-shelf small models such as TinyLLaMA-1.1B (or even the larger Wizard-2-7B model) are not able to output the correct plans. The errors ranged from problems such as using the wrong set of functions, hallucinated names, wrong dependencies, inconsistent syntax, etc.

This is rather expected because these small models have been trained on generic datasets and primarily targeted to achieve good accuracy on general benchmarks which mostly test the model’s world knowledge and general reasoning or basic instruction following capability. To address this, we explored if fine-tuning these models on a high-quality dataset specially curated for function calling and planning can improve the accuracy of these small language models for a targeted task, potentially outperforming larger models. Next, we first discuss how we generated such a dataset, and then discuss the fine tuning approach.

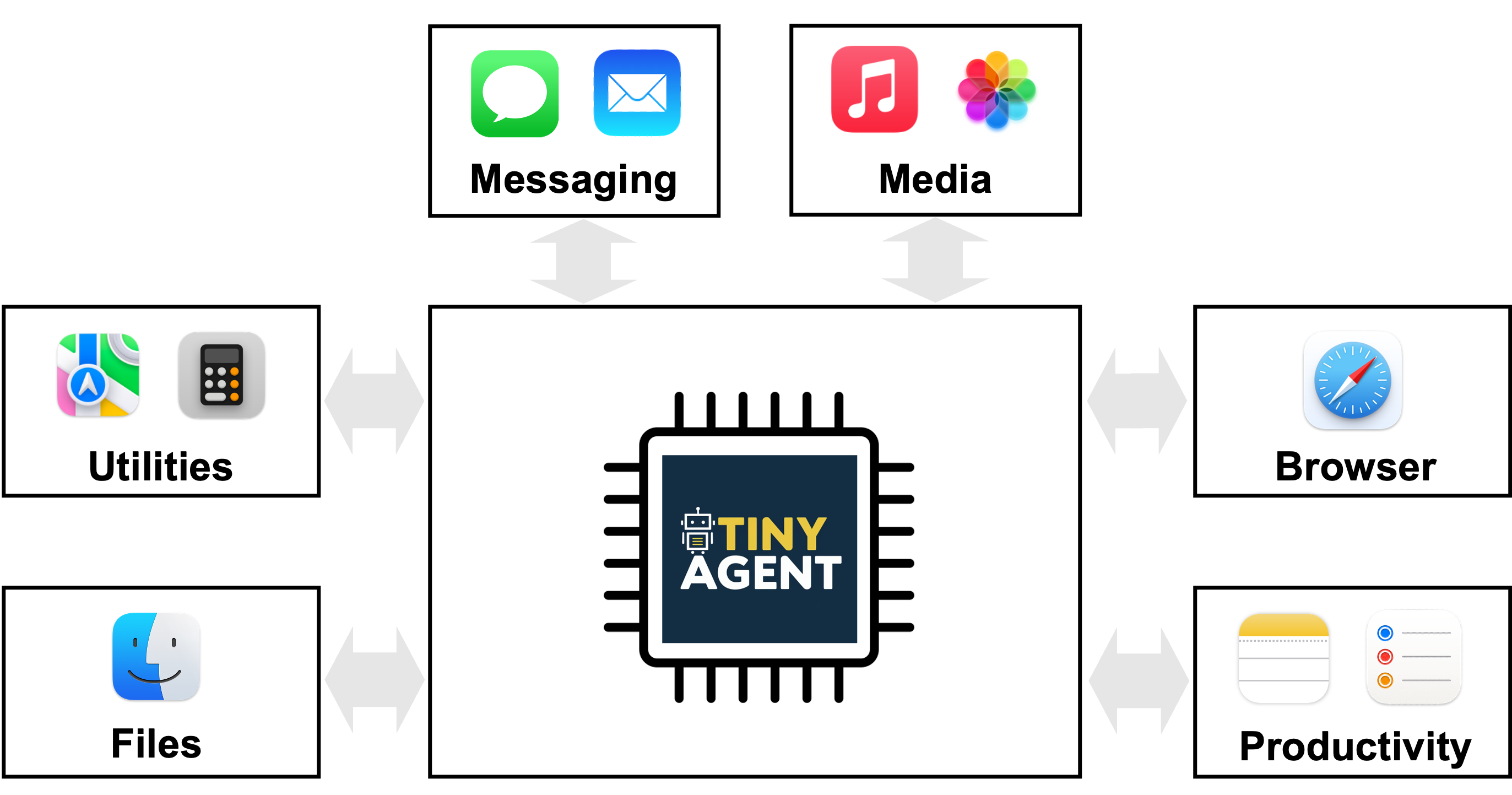

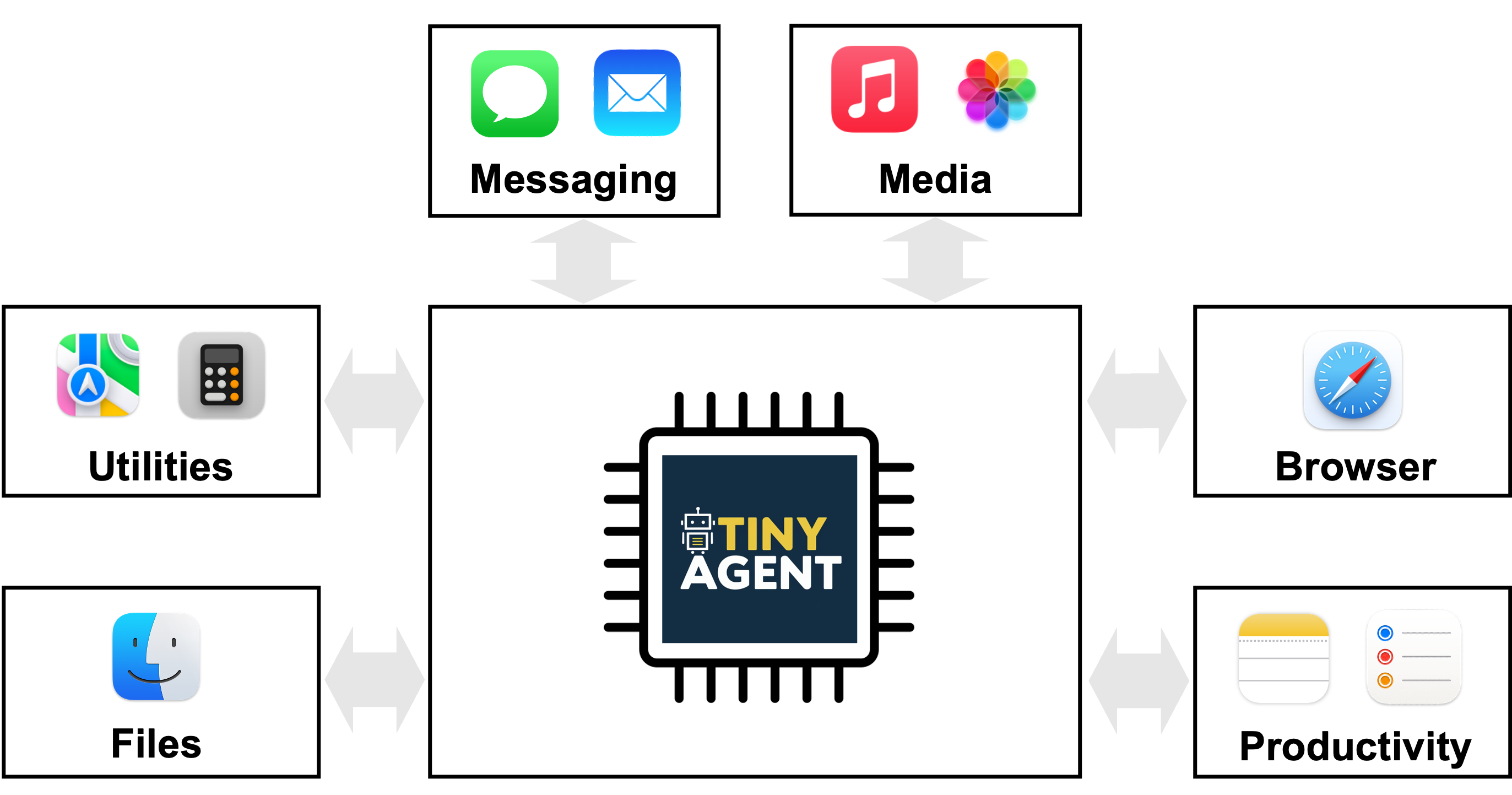

Figure 2: TinyAgent is an assistant that can interact with various MacOS applications to assist the user. The commands can be given to it through either text through a spotlight input, or through voice.

As a driving application, we consider a local agentic system for Apple’s Macbook that solves user’s day-to-day tasks, as shown in Figure 2. Particularly, the agent is equipped with 16 different functions that can interact with different applications on Mac, which includes:

- Email: Compose a new email or reply to/forward emails

- Contacts: Retrieve phone numbers or email addresses from the contacts database

- SMS: Send text messages to contact(s)

- Calendar: Create calendar events with details such as title, time, attendees, etc.

- Notes: Create, open, or append content to notes in various folders

- Reminder: Set reminders for various activities and tasks

- File management: Open, read, or summarize documents in various file paths

- Zoom meetings: Schedule and organize Zoom meetings

Predefined Apple scripts exist for each of these functions/tools, and all that the model needs to do is to take advantage of the predefined APIs and determine the right function calling plan to accomplish a given task, such as in Figure 1. But as discussed previously, we need some data for evaluating and training small language models since their off-the-shelf function calling capability is subpar.

Creating handcrafted data with diverse function calling plans is both challenging and not scalable. However, we can curate synthetic data using an LLM like GPT-4-Turbo. Such an approach is becoming a common method where a capable LLM is instructed to generate data similar to a given set of sample examples or templates (see LLM2LLM and Self-Instruct). In our work, we used a similar approach, but instead of providing the LLM with generic user queries as templates, we provide it with various sets of functions and instruct it to generate realistic user queries that require those functions to accomplish the task, along with the associated function calling plan and input arguments, like the example shown in Figure 1. To verify the validity of the generated data, we incorporated sanity checks on the function calling plan to make sure that they form a feasible graph, and that the function names and input argument types are correct. With this approach, we created 80K training data, 1K validation data, and 1K testing data, with a total cost of only ~$500.

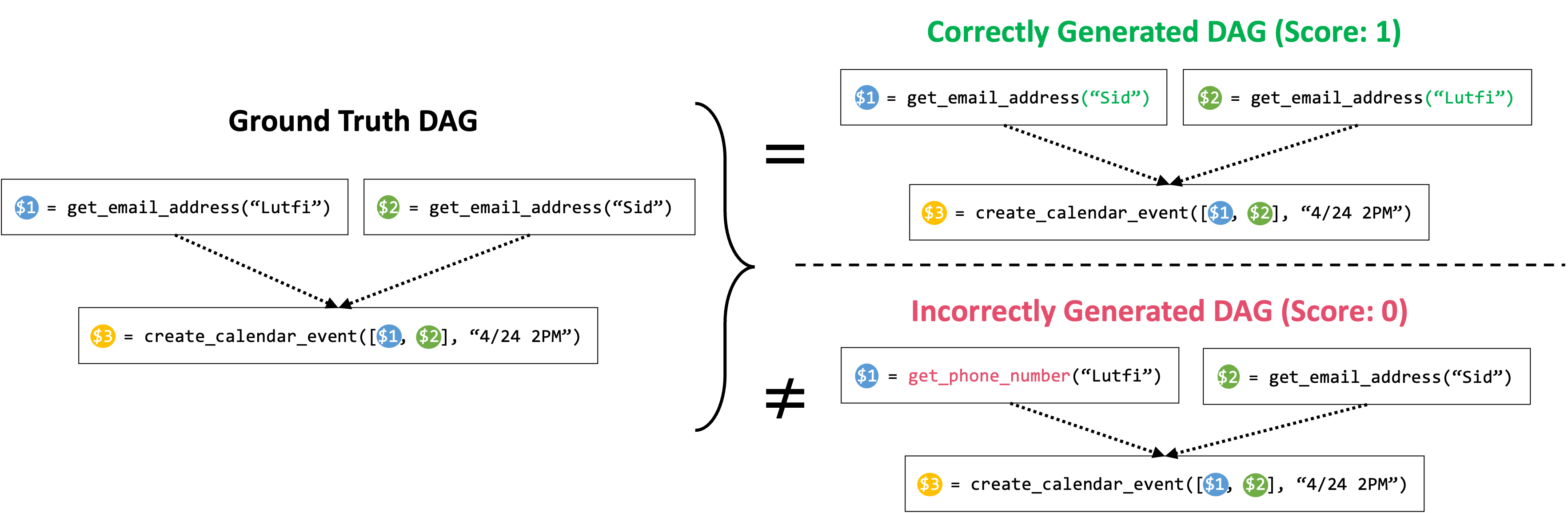

Figure 3: Graph Isomorphism Success Rate. The model scores a success rate of 1 only if the DAG of its generated plan is isomorphic to the DAG of the ground truth plan; and 0 otherwise. In above example, for the top case, although the order of the get_email_address calls are different from the ground truth plan (the ground truth plan gets the email address of Lutfi before Sid, and the generated plan gets the email address of Sid before Lutfi), since the two DAGs are isomorphic to each other, the plan gets 1 success rate. For the bottom case, since the predicted DAG contains a wrong node, corresponding to a wrong function call, the plan gets 0 success rate.

With our dataset in place, we can now proceed to fine-tune off-the-shelf SLMs to enhance their function calling capability. We started with two base small models: TinyLlama-1.1B (instruct-32k version) and Wizard-2-7B. For fine-tuning these models, we first need to define a metric to evaluate their performance. Our objective is for these models to accurately generate the right plan, which involves not only selecting the right set of functions, but also correctly orchestrating them in the right order. Therefore, we define a success rate metric that assigns 1 if both criteria are met, and 0 otherwise. Checking whether the model has selected the right set function calls is straightforward. To additionally ensure that the orchestration of these functions is correct, we construct a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) of the function calls based on the dependencies, as shown in Figure 3, where each node represents a function call and a directed edge from node A to B represents their interdependency (i.e. function B can only be executed after the execution of function A). Then we compare if this DAG is identical to that of the ground truth plan to verify the accuracy of the dependencies.

After defining our evaluation metric, we applied LoRA to fine-tune the models for 3 epochs using a learning rate of 7e-5 over the 80K training examples, and selected the best checkpoint based on validation performance. For fine-tuning, our prompt included not only the descriptions of the ground truth functions (i.e. functions used in the ground truth plan) but also other irrelevant functions as negative samples. We found the negative samples to be particularly effective for teaching the model how to select appropriate tools for a given query, hence improving the post-training performance. Furthermore, we also include several in-context examples demonstrating how queries are translated into a function calling plans. These in-context examples are selected through a Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) process based on the user query from the data in the training dataset.

Using the above settings, we fine-tuned TinyLlama-1.1B/Wizard-2-7B models. After fine-tuning, the 1.1B model improved the success rate from 12.71% to 78.89%, and the 7B model performance improved from 41.25% to 83.09%, which is ~4% higher than GPT-4-Turbo.

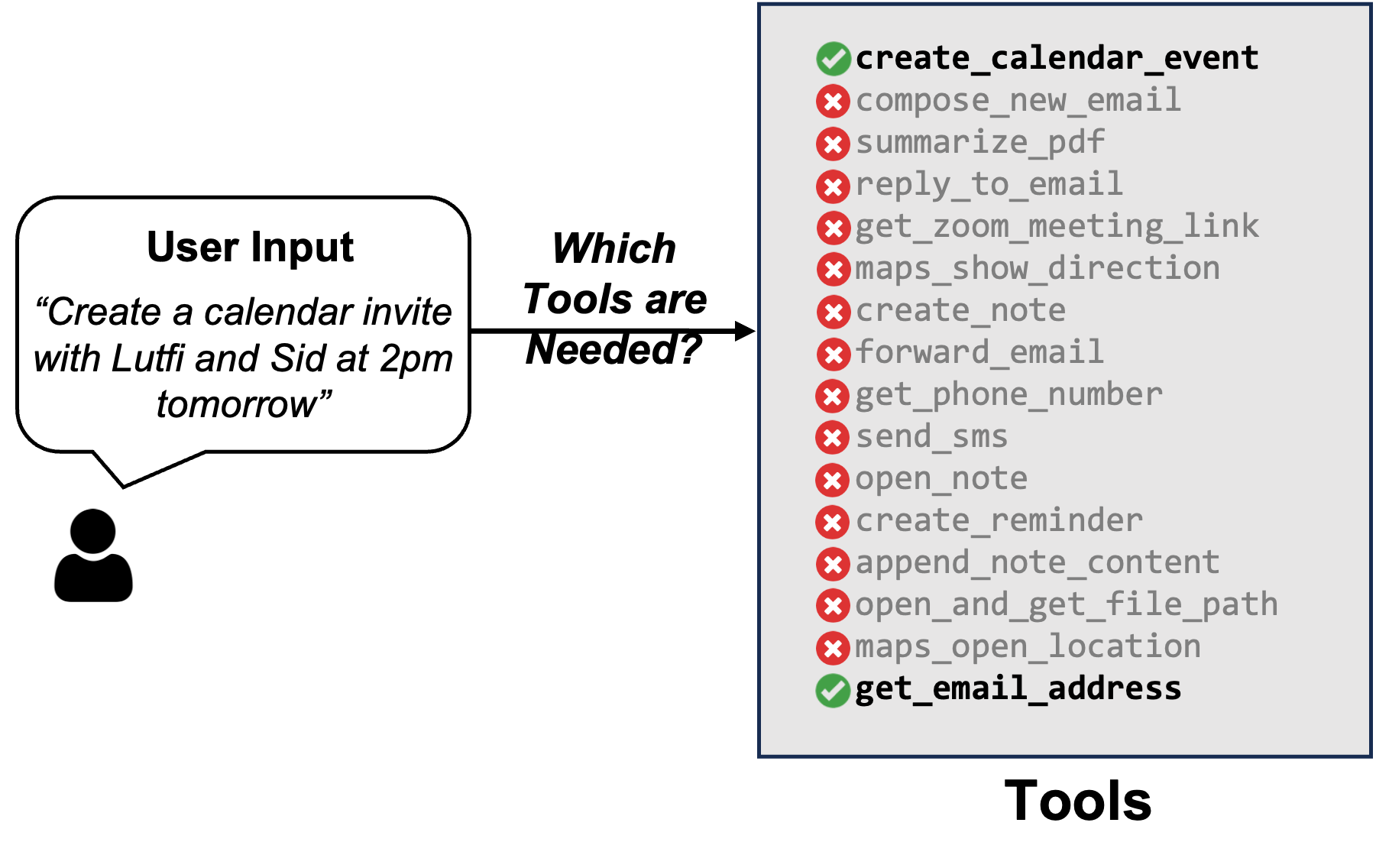

Figure 4: Efficient Tool Selection Based on User Input. Not all user inputs require all available tools; hence, it is imperative to select the right set of tools to minimize the prompt size and increase performance. In this case, the LLM only needs the functions that get email addresses and create a calendar event in its prompt to accomplish its task.

Our primary goal is to be able to deploy the TinyAgent model locally on a Macbook, which has limited computational and memory resources available as compared to the GPUs that closed-source models like GPT are deployed on. To achieve efficient performance with low latency we need to ensure that not only the model size is small, but that the input prompt is as concise as possible. The latter is an important contributor to latency and computational resource consumption due to the quadratic complexity of attention on sequence length.

The fine-tuned TinyAgent model discussed previously was fine-tuned with the description of all available tools in its prompt. However, this is pretty inefficient. We can significantly reduce the prompt size by only including the description of relevant tools based on the user query. For instance, consider the example shown in Figure 4 above, where the user is asking to create a calendar invite with two people. In this case, the LLM only needs the functions that get email addresses and create a calendar event in its prompt.

To take advantage of this observation, we need to determine which functions are required to accomplish the user’s command, which we refer to as Tool RAG given its similarity with how Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) works. However, there is an important subtlety. If we use a basic RAG method where we compute the embedding of the user query and use that to retrieve the relevant tools, we get very low performance. This is because completing a user’s query often requires using several auxiliary tools which may be missed with a simple RAG method if the embedding of the auxiliary tool is not similar to the user query. For instance, the example shown in Figure 4 requires calling get_email_address function even though the user query is just asking about creating a calendar invitation.

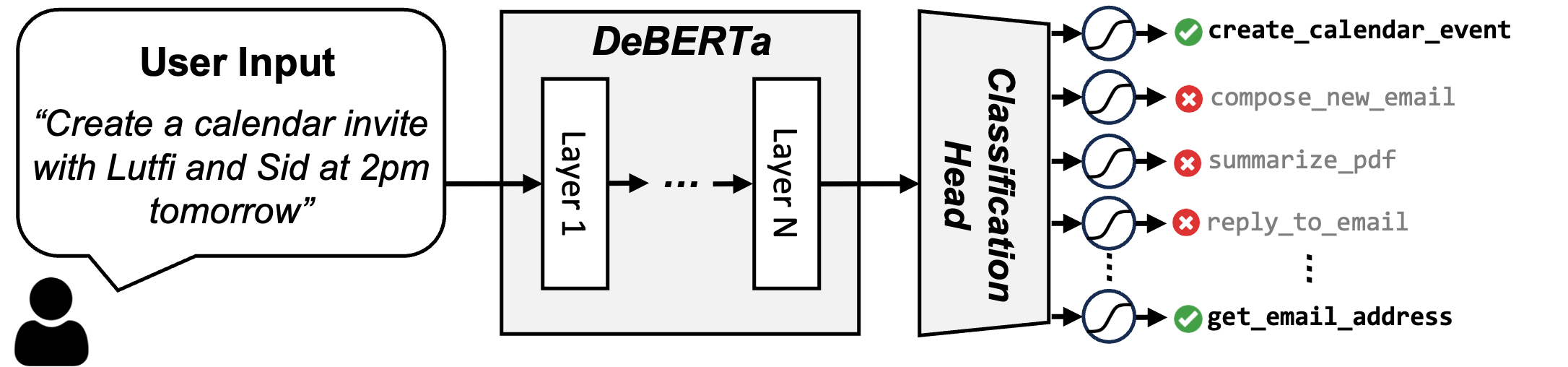

This can be addressed by treating the problem as a classification of which tools are needed. To that end, we fine-tuned a DeBERTa-v3-small model on the training data to perform a 16-way classification as shown in Figure 5. The user query is given as an input to this model, and then we pass the CLS token at the end through a simple fully connected layer of size 768×16 to transform it into a 16 dimensional vector (which is the total size of our tools). The output of this layer is passed through a sigmoid layer to produce the probability of selecting each tool. During inference, we select the tools that have probably higher than 50%, and if so, we include their description in the prompt. On average we noticed that only 3.97 tools are retrieved with a recall of 0.998, whereas the basic RAG requires using the top 6 tools to achieve a tool recall of 0.968.

Figure 5: Overview of our Tool RAG scheme. We formulate tool retrieval as a multi-label classification problem. The user query is given as input to the fine-tuned DeBERTa-v3-small model, which outputs a 16-dimensional vector indicating tool probabilities. Tools with probabilities higher than 50% are selected, averaging 3.97 tools per query compared to 6 tools in basic RAG.

We evaluated the model performance after incorporating Tool RAG. The results are shown in Table 1 below, where we report the performance of the simple RAG system along with the fine-tuned DeBERTa approach. As one can see, the DeBERTa based Tool RAG method achieves almost perfect recall performance, improves the baseline accuracy, while reducing the prompt size by ~2x tokens.

Table 1: Comparison of TinyAgent performance with DeBERTa to Basic RAG and no RAG settings.

| Tool RAG Method | Tool Recall | Prompt Size (Tokens) | TinyAgent 1.1B Success Rate (%) | TinyAgent 7B Success Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No RAG (all tools in the prompt) | 1 | 2762 | 78.89 | 83.09 |

| Basic RAG | 0.949 (top 3) | 1674 | 74.88 | 78.50 |

| Fine-tuned DeBERTa-v3-small (Ours) | 0.998 (tools with >50% prob) | 1397 | 80.06 | 84.95 |

Deploying models at the edge, such as on consumer MacBooks, can still be challenging even for small models of O(1B) parameters, since loading the model parameters can consume a large portion of the available memory. A solution to these issues is quantization, which allows us to store the model at a reduced bit precision. Quantization not only reduces the storage requirements and model footprint, but also cuts down the time and resources needed to load model weights into memory, thereby reducing the overall inference latency as well (see this for more information on quantization).

For more efficient deployment of the models, we quantized the models into 4-bit with a group size of 32, which is supported by the llama.cpp framework with quantization aware training. As shown in Table 2, the 4-bit models result in 30% better latency, along with a 4x reduction in the model size. We also notice slight accuracy improvement which is due to the additional fine-tuning with simulated quantization.

Table 2: Latency, size, and success rate of TinyAgent models before and after quantization. Latency is the end-to-end latency of the function calling planner, including the prompt processing time and generation.

| Model | Weight Precision | Latency (seconds) | Model Size (GB) | Success Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-3.5 | Unknown | 3.2 | Unknown | 65.04 |

| GPT-4-Turbo | Unknown | 3.9 | Unknown | 79.08 |

| TinyAgent-1.1B | 16 | 3.9 | 2.2 | 80.06 |

| TinyAgent-1.1B | 4 | 2.9 | 0.68 | 80.35 |

| TinyAgent-7B | 16 | 19.5 | 14.5 | 84.95 |

| TinyAgent-7B | 4 | 13.1 | 4.37 | 85.14 |

Below is the demo of the final TinyAgent-1.1B model deployed on a Macbook Pro M3 which you can actually download and install on your Mac and test as well. It not only runs all of the model inference locally on your computer, but it also allows you to provide commands through audio. We process the audio locally as well using the Whisper-v3 model from OpenAI deployed locally using the whisper.cpp framework. The greatest surprise for us was that the accuracy of the 1.1B model exceeds that of GPT-4-Turbo, and is markedly fast while deployed locally and privately on device.

To summarize, we introduced TinyAgent and showed that it is indeed possible to train a small language model and use it to power a semantic system that processes user queries. In particular, we considered a Siri-like assistant for Mac as a driving application. The key components for enabling it is to (i) teach off-the-shelf SLMs to perform function calling through LLMCompiler framework, (ii) curate high quality function calling data for the task at hand, (iii) fine-tune the off-the-shelf model on the generated data, and (iv) enable efficient deployment by optimizing the prompt size through only retrieving the necessary tools based on the user query through a method called ToolRAG, as well as quantized model deployment to reduce inference resource consumption. After these steps, our final models achieved 80.06% and 84.95% for the TinyAgent1.1.B and 7B models which exceed GPT-4-Turbo’s success rate of 79.08% on this task.

We would like to thank Apple for sponsoring BAIR lab. We also thank Sunjin Choi for his insights in energy cost associated with local and cloud deployment. Our conclusions do not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of our sponsors, and no official endorsement should be inferred.