Introduction

Few types of media hook me like a good documentary. The genre uses the best elements of traditional filmmaking to amplify what will always be the greatest story ever told: reality. Whether it’s an educational look at the natural world, a gripping true crime tale, or an enlightening biography of a noteworthy figure, the best documentaries manage to educate as effectively as they entertain.

The video games industry is now old enough to have been subjected to its fair share of documentaries, from The King of Kong to Indie Game: The Movie to Netflix’s High Score. But no matter how good they are, they all generate a tough-to-pin-down anxiety in me I never consciously noticed until recently: By the time the film ends, or, more often, in the middle of it, I just want to stop watching and play the games in question.

It’s a frustration shared by Chris Kohler, the editorial director at Digital Eclipse. And it’s one of the reasons why he enjoys working on the studio’s Gold Master Series. Essentially the gaming equivalent of the Criterion Collection, it consists of two titles, The Making of Karateka and Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story. Each game takes players on a playable history lesson of its subjects, be it a single game, a creator, or an entire studio. The result is a new genre Digital Eclipse can call its own: the interactive documentary.

Digital Eclipse’s neon-lit arcade

Built On Preservation

Built On Preservation

Digital Eclipse has led the charge in commercial video game emulation since its early years. Founded in 1992 as Williams Digital Arcade, it specialized in creating arcade-accurate console ports of classic arcade titles via emulation at a time when this was mainly accomplished by replicating an arcade game’s code from scratch.

“It was if you went and bought The Godfather on VHS, and it was just new people trying to recreate the version of The Godfather that was on film instead of somebody coming up with technology that would allow you to take a filmstrip and get that information onto a Blu-ray or DVD or whatever it is,” Kohler explains.

Digital Eclipse is a pioneer in commercial emulation. While the studio’s methods equated to a more enjoyable gaming experience, it also served as an early example of game preservation. Kohler says the company was essentially built on the need to pay retro games the proper respect.

Atari 50: The Anniversary Celebration

The 2000s saw the company undergo a complicated period of mergers and rebrands before reemerging in 2015 as Digital Eclipse once more. This saw the studio shift its focus back towards preservation in the form of retro game compilations such as the Mega Man Legacy Collection, Disney Afternoon Collection, and Street Fighter 30th Anniversary Collection. These titles included bonus features such as long-lost concept art and other development and marketing materials that, with each release, gradually grew from being a sideshow to almost the main attraction.

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: The Cowabunga Collection, released in 2022, is perhaps the most impressive of these game bundles. In addition to packing in 13 old-school TMNT games, it boasts an exhaustive number of forgotten materials such as original magazine ads, scans of the original game boxes and manuals, comic book covers, and never-before-seen concept art. For ’80s babies, they weren’t just revisiting old TMNT games; they were reliving the franchises’ early pop-culture boom while getting a behind-the-scenes look at how these games were brought to life.

While retro collections help keep old games alive, Kohler says they only offer the “What” of a game’s overall history. They don’t provide the “Who,” “Where,” “How,” and, most importantly, the “Why.” To fill those gaps, Digital Eclipse needed a fresh approach.

Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story

Creating A Genre

Creating A Genre

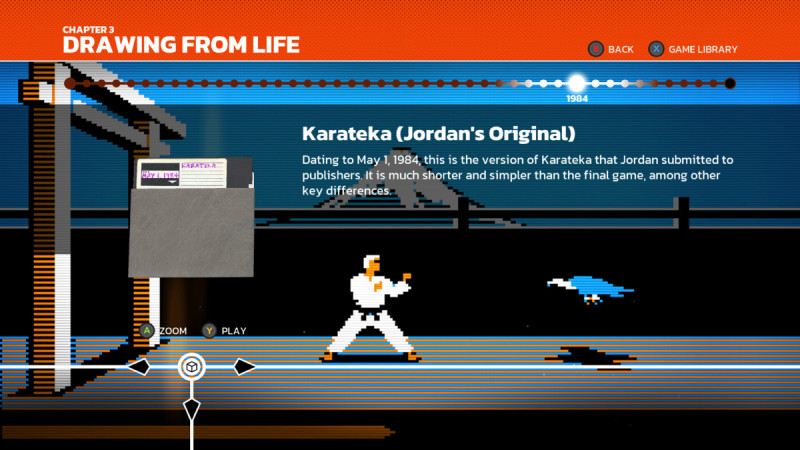

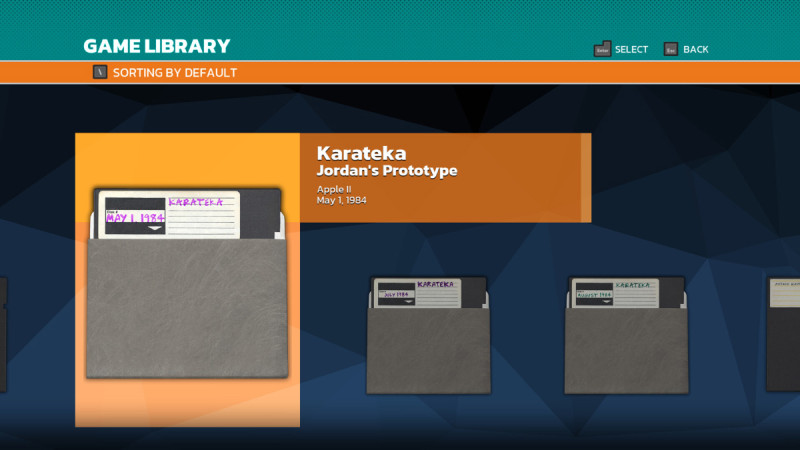

Kohler joined Digital Eclipse in July 2020. At the time, the company had licensed the Karateka IP from creator Jordan Mechner to create a new retro collection of sorts. Unlike its previous projects, Digital Eclipse had full control over the Karateka game’s direction since the studio didn’t have to work with a publisher. The Karateka title became Kohler’s first major project, and the team also gained access to years’ worth of Mechner’s personal materials. These included his journals documenting his daily life while developing Karateka, design documents, publisher correspondences, and more. As Kohler pored over decades-old legal negotiations and Mechner’s written insights into creating Karateka and other games, he and the team saw the potential to tell Karateka’s story in a new fashion.

“And just realizing that there was this incredible narrative behind this game, and because we had Jordanʼs journals where he was writing down day by day everything that was happening in his life as he was creating this game, we could really go far beyond the idea of the retro collection,” says Kohler. “We could really tell this in a narrative way, and the story itself can become the main event, as it were.”

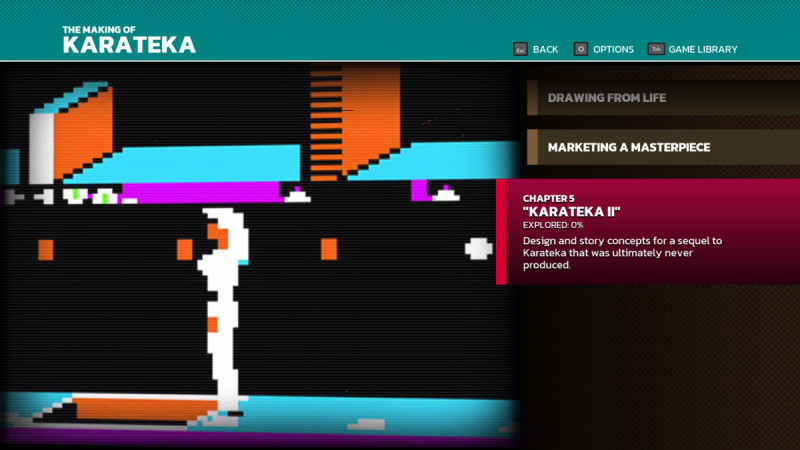

The Making of Karateka

The seed for the interactive documentary had been sewn, and the team began brainstorming. What if they could tell a linear story that takes players down the complete timeline of a game’s development? Better yet, what if players could play not only the finished product but also its various prototypes?

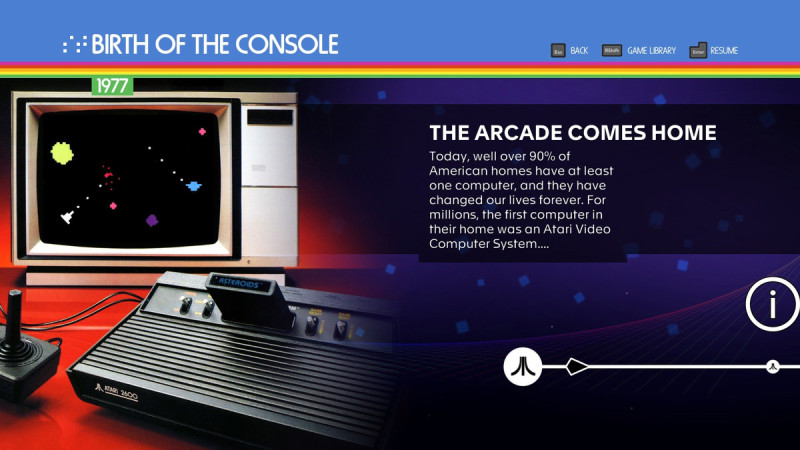

It was around this time that Digital Eclipse began a partnership with Atari to create a title celebrating the companyʼs 50th anniversary. Coincidentally, Atari wanted something different than the average retro collection, and Digital Eclipse saw this as the perfect opportunity to implement its nascent documentary game concept. The idea that was originally envisioned for The Making of Karateka would make its debut in Atari 50: The Anniversary Collection.

In addition to conducting a staggering amount of research, Digital Eclipse filmed interviews with former Atari employees and industry luminaries. Perhaps most impressively, it included over 100 playable Atari games, from the iconic to the forgotten, via emulation. The result was a robust story of Atari’s founding and golden age told through linear timelines divided by chapters. Players read informative blurbs, viewed development documents and other key materials, watched documentary clips, and, of course, played the games that define a generation. As a bonus, it had even developed modern reimaginings of select titles.

Digital Eclipse CSO and Head of Publishing Justin Bailey summons Karateka’s dreaded hawk at the Portland Retro Expo

The result was a resounding success. Atari 50 earned widespread acclaim as one of the most complete and well-made video game compilations ever created. It also worked as a successful proof-of-concept for the fledgling interactive documentary concept.

“By taking that all the way to the finish line, we were able to kind of work out the structure and the format,” says Kohler. “And as weʼre kind of getting towards the end of Atari 50, it was like, ‘Okay, now itʼs time to take all these learnings that weʼve had by finishing out Atari 50 and then revisit that back on to Karateka.’”

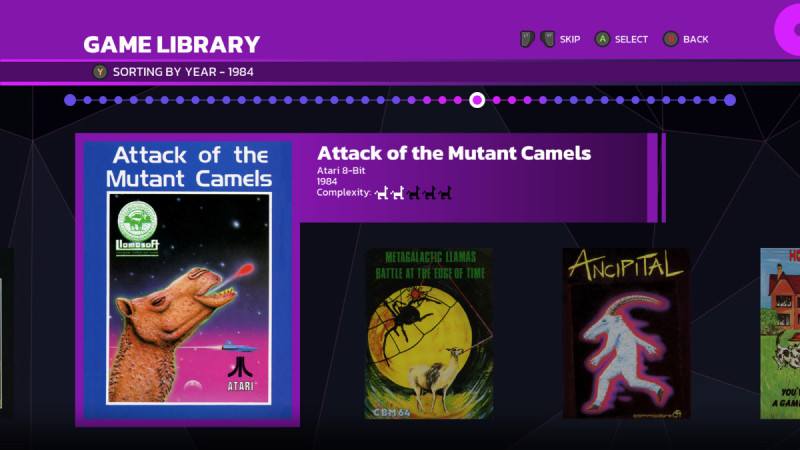

By this time, Digital Eclipse had also signed on with famed UK developer Jeff Minter, creator of hits such as Gridrunner and Tempest 2000, for a title documenting his studio, Llamasoft. Thanks to Atari 50, Digital Eclipse found a winning formula for telling more great stories from video game history. The Gold Master Series was born as a result, and The Making of Karateka and Llamasoft adhered to Atari 50’s blueprint to tell their respective stories and expand players’ appreciation for them.

Reshaping History

Reshaping History

“Nobodyʼs really doing what weʼre doing,” says Kohler. “And maybe for good reason. Maybe weʼre crazy, but weʼre doing our best to try to figure out what this new type of video game is.”

The Gold Master Series team consists of former game journalists like Kohler and Dan Amrich, who handle the lion’s share of researching and crafting the resulting narratives. The games are made using the Eclipse Engine, proprietary software specially designed to easily ingest emulators, either licensed or developed in-house, to run several old games from a plethora of platforms. The Eclipse Engine is the secret sauce of the Gold Master Series, as its ability to juggle emulators alongside sound and video in a fast and responsive manner is the reason why navigating the games’ timelines feels smooth and snappy.

Of course, each game needs a central topic, and everyone at Digital Eclipse, as you might expect, has a personal wishlist of subjects. “Iʼm still waiting for that call from Shigeru Miyamoto,” says Kohler. “He has my number.” I found it hard to think that anyone could top Jordan Mechner. His absurdly meticulous note and record keeping (Kohler: “Nobody’s that organized! Who does that?!”) makes him the gold standard when it comes to providing enough reference material to fill a game. But Kohler tells me that so long as the subject is interesting/important, how much they choose to hold on to isn’t a prerequisite to be considered for a Gold Master Series game. If Digital Eclipse needs something, one way or another, they’ll find it. And whatever they gather will shape the game accordingly. Jeff Minter didn’t have as many design documents as Mechner, so Digital Eclipse leaned more into showing what the actual games looked like. Llamasoft includes models of the cassette tapes along with advertisements and reviews from UK gaming mags at the time. Some materials aren’t found until close to the end of production.

Atari 50, for example, had to be patched to include film footage recorded by a Berkeley University student of Atari back when the company was still called Syzygy. Essentially an amateur documentary capturing the birth of Atari, the footage vanished for decades. While the Atari Museum possessed a copy of the film, Digital Eclipse didn’t have the rights to use it. So, instead, the studio had to track down one of the students who made it, get their permission to use their footage, research the legal rights for its commercial use, and patch it into Atari 50 after it was already finalized. “We did so much legwork to get that little like, two, three minutes snippet of a film in this,” says Kohler.

Battlezone designer Owen Rubin at his controller-laden work station

That effort speaks to the length Digital Eclipse will go to ensure its interactive documentaries are as rich and comprehensive as possible. “We have not had a situation yet where weʼve wanted to tell a story and have not been able to find cool things to tell that story,” Kohler says. “So, I donʼt think we ever will. I think we can find the things.”

The closest comparison I offer for the Gold Master Series is they feel like modern museum exhibits. A museum attendee can breeze through exhibits, giving little more than cursory glances, and walk away with a basic understanding of the history lesson told. Conversely, they can read every card, press every button, and play every video to absorb more details. Kohler says Digital Eclipse wants the Gold Master Series to offer the same range of engagement and that either approach, no matter how shallow or deep, is perfectly okay.

Additionally, Digital Eclipse is always looking for ways to add interactivity beyond just playing an emulated game. One great example is The Making of Karateka’s rotoscope theater, where players can watch a short clip of the game while toggling each animation layer, almost like Photoshop filters. In fact, Kohler cites the rotoscope theater as an example of how Digital Eclipse has only scratched the surface of what the interactive documentary can evolve into. That leads to the million-dollar question: Does he consider these types of experiences to be true video games?

‘Yes, I think itʼs a video game,” Kohler explains. “I think itʼs a video game as much as [a] documentary film is a film. And I think that in the same way that filmmakers and film critics back in the ’70s kind of started looking at film and saying, ‘We should be talking about film by making films about film,’ we should be talking about video games by making video games about video games.”

Writing The Next Chapter

Writing The Next Chapter

Kohler says Digital Eclipse regularly receives feedback that players unfamiliar or unattached to the subject of the Gold Master Series are less willing to give them a shot. It’s a constant challenge to communicate that not only has Digital Eclipse made these games with such people in mind, but you’ll likely walk away with a newfound appreciation or even fandom for the games being discussed.

“I think it all goes back to the fact that video games are just such a new medium,” he says. “And weʼre only sort of just scratching the surface of what could be done with that interactive medium.”

Despite this, Kohler says he believes that if Digital Eclipse keeps doing the work, eventually, they’ll attract enough attention to break through to a wider audience. At the end of the day, he believes people do enjoy being educated, as evidenced by the popularity of more traditional documentary-style programs and podcasts. In his eyes, the Gold Master Series isn’t just about teaching – he refers to the term “edutainment” as being “tainted” – but also about bringing more nonfiction into the medium of video games.

The Making of Karateka exhibit at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

The Gold Master Series titles have unintentionally been released at a cadence of one per year (Llamasoft in 2024, Karateka in 2023, and their spiritual predecessor Atari 50 in 2022). Kohler says not to expect this pattern to continue, but the team has various projects in the works. Atari’s acquisition of Digital Eclipse in the fall of 2023 has presumably provided a stronger financial safety net, so I only hope we have many more Gold Master Series games to come. And while Kohler is hopeful, he also doesn’t want Digital Eclipse to monopolize the genre. He hopes their work creates enough of a demand to inspire other studios to pursue similar projects.

“We should be telling our own stories,” he says. “We shouldnʼt be letting books and films or a Netflix series tell the stories of video games. We should be looking at that ourselves because itʼs all part of the video game industry needing to treat video games with more respect.”

This article originally appeared in Issue 366 of Game Informer