Before we read and wrote, we moved. Stories of people moving – migrating – have been told since time immemorial. The Mexica journey to central Mexico; Moses leading the Jewish people across the desert; the founding of Rome – as told by Virgil – by those that fled the fall of Troy. Unsurprisingly, then, video games also tell stories of migration. On August 8, 2013, game designer Lucas Pope, the man behind the studio 3909, released Papers, Please, a game about managing migration.

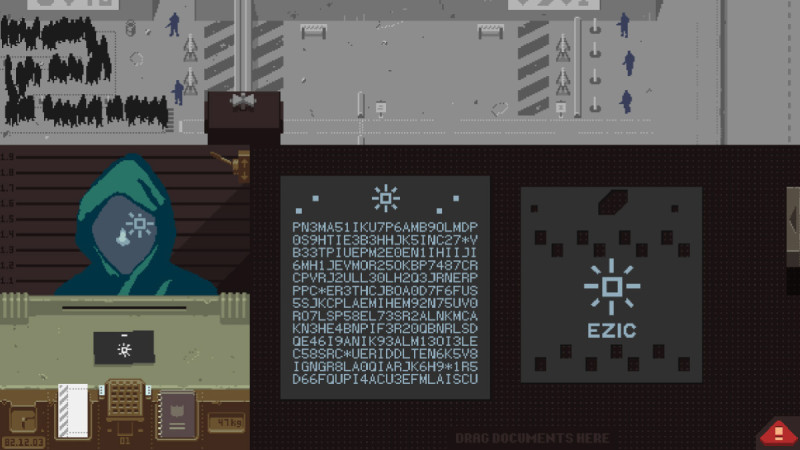

Papers, Please, subtitled “A Dystopian Document Thriller,” was for some the first time they played a game whose core design ethos challenged their worldviews and understanding. Other games have placed the topic of migration front and center. Path Out (Causa Creations, 2014), an adventure game that retells the journey of Abdullah Karam, a young Syrian artist who escapes the country’s decade-long civil war in 2014; and Escape from Woomera (2003), a game about a refugee, Mustafa, stuck in the infamous Woomera Immigration Reception and Processing Centre in South Australia, are two stand-outs. Papers, Please tackles the subject from a different perspective. You play an inspector examining documents, determining whether a person can enter the fictional country of Arstotzka.

A decade after its release, the bureaucratic nightmare in Papers, Please is an increasing reality for many around the world. We see this on the news: anguished faces looking for prospects either fleeing war, environmental catastrophe, or lack of economic and social opportunities. According to the Migration Policy Institute, at the end of 2022, over 100 million people were displaced globally. Along with revisiting Papers, Please, I interviewed Pope for his perspective on the game 10 years on. I also talked to former United States diplomat Josef Burton, who worked in several consulates and embassies around the world processing visa applications, for his thoughts on the game.

Papers, Please is an odd commercial success. According to Pope, the indie game sold over five million copies across all platforms between August 8, 2013 and August 8, 2023. It also received numerous awards and acclaim from players and critics alike. It’s one of only 36 video games in the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection, alongside Tetris, Street Fighter II, and Portal. Pope feels he owes his career to the game. “It’s hard to look back and be anything but proud of it,” he says. “It’s not perfect, and maintaining it for 10 years gave me a good look at that, but I still consider it my best work so far.” High praise considering Pope also released the critically acclaimed Return of the Obra Dinn in 2018.

The game’s visuals and themes are heavily influenced by the last decade of the Cold War. Its story shares much in common with the books of John le Carré, where spies – really just bureaucrats – are placed in impossible situations within geo-political struggles with grand implications. Most don’t survive. If they do, the price paid for completing their work is often too high. The same is true of The Inspector in Papers, Please. The game turns the player into a villain or anti-hero.

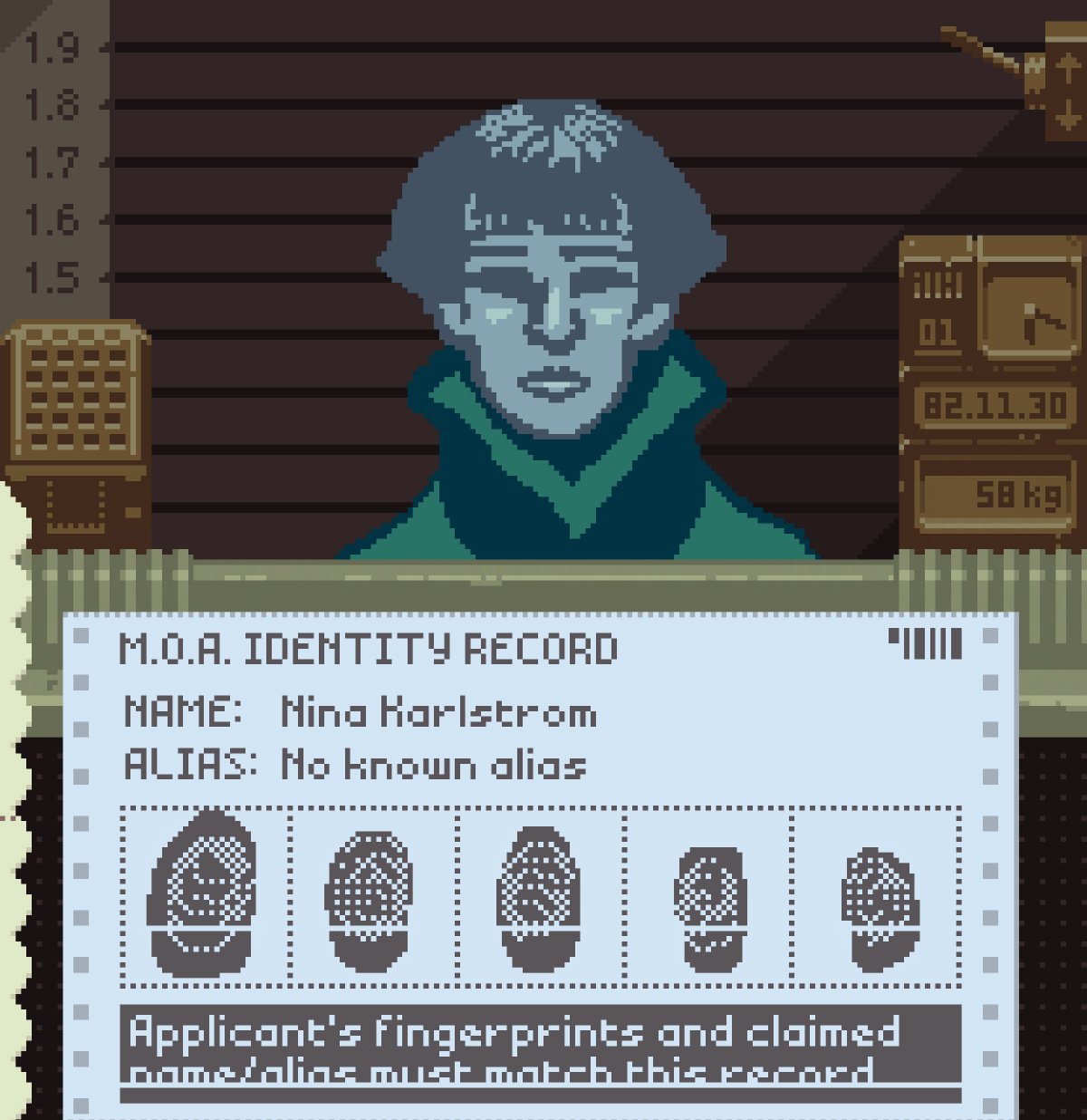

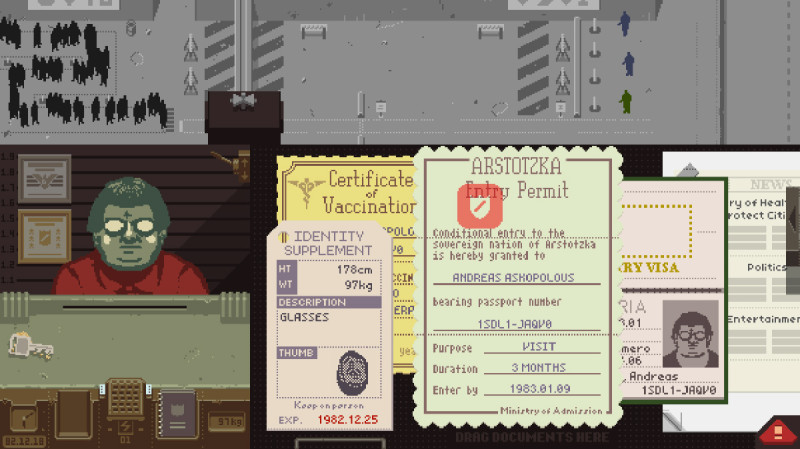

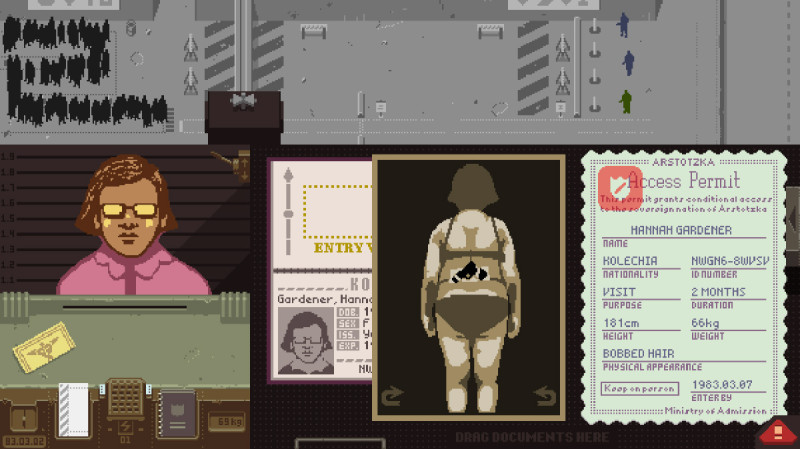

At the beginning of the game, progress depends on how well you follow a handbook of rules and regulations created by Arstotzka’s Ministry of Admission. As you play, the work of Custom and Border Protection officials stops being an abstraction. Players must protect the border and not allow those unauthorized by the Arstotzka’s Ministry of Admission to enter; thus, you make cold and crucial determinations about people’s futures. This sort of determination is made every day across borders all over the real world.

Migration stories are enthralling. Migrants, refugees, and asylees are – in the sincerest sense of the word – the first entrepreneurs. Papers, Please is an important game because it contextualizes the broader issues relating to migration enforcement in a visceral and tangible way. The point is not to moralize but to tell a story via interactive means. Players who can stomach playing as the inspector get a view of Pope’s vision of a dystopian altered reality inspired by former Communist Bloc nations.

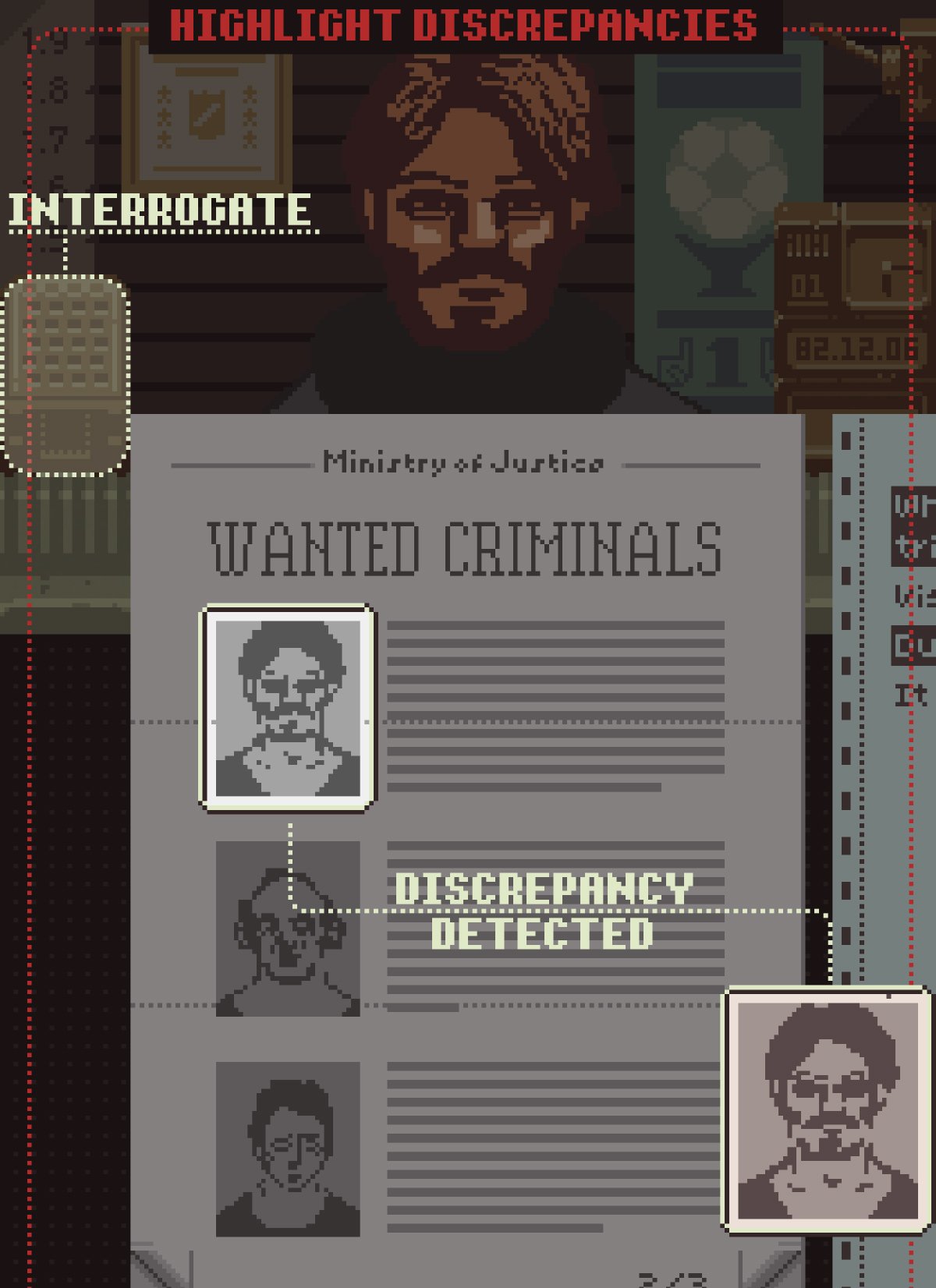

Burton has mixed feelings about the game and its portrayal of immigration control. “The fantasy of Papers, Please is brutal because you’re this inhuman bureaucrat,” he says. “There’s this plotting, droning music […] and there is this dystopic kind of feeling like in the first level of Half-Life 2. You’re like, ‘No, absolutely not! Let’s examine your papers. You don’t have enough papers.’ I think that we’ve departed from that. What I would take away from my time at the State Department, in the Foreign Service, and in Consular Affairs is that it’s much more insidious than you would think. In seven and a half years, I only caught one person based on just documents. And that case was a really sloppy attempt at identity theft.”

Pope does not claim that Papers, Please represents the complexities of international immigration policy “in anything other than a vastly simplified way.” Ultimately, he chose to highlight “some of the bigger talking points, and there are hints of real-world associations, but to keep things flexible, I figured it was best to not follow reality too closely.”

Looking back, Pope adds, “When I made the game in 2013, immigration as a topic was in the news but felt to me like an issue that had made some recent progress and was on track to get better. Unfortunately, that was all an illusion – the situation for immigrants and refugees has only gotten worse since then. In a perfect world, the game would’ve fallen out of relevance immediately, and we wouldn’t be talking about it anymore.”

Papers, Please is a Cold War tale. When I first played the game, the opening lyrics of Yellow Magic Orchestra’s song “Ballet” played in my head. “Turning faded pages…She was a refugee from across the wall. Acting out a story written in Air.” You turn a lot of paper in the game. You also can’t help but make up stories about each person who appears at your window to present their passports and other documents.

For Pope, the entire premise was “…mostly inspired by the mechanical side of the game’s design. Just moving the papers around was fun for me personally, and so I did my best to build on that. What kinds of things would a resource-limited border inspector see? How would they be expected to react? How can these activities be turned into interesting things for the player to do? The concept and setting were enough to keep the ideas coming until I felt like I had a whole game.”

The earnestness of Papers, Please, overwhelms players. Waiting in line to be interviewed by an immigration official brings with it a feeling of uncertainty, maybe even insecurity. Readers of the German sociologist Max Weber might be familiar with how bureaucracy is dehumanizing by design. It must be impersonal to function at a large scale. Welcome to the machine. Pope doesn’t take this aspect of the system for granted.

Papers, Please forces players to make unethical decisions. I asked Pope what the gameplay loop at the heart of the game says about migration and border control. He responded, “Something I tried to capture in the game is the dehumanizing aspect of bureaucracy. I think border control is a good example of how rules made in one place in response to a political issue really look when they reach the actual people that enforce them and the people that are affected by them. Those bureaucracy-driven elements were convenient for the design too, where rules can change from day to day arbitrarily to ratchet up the pressure or direct the story.”

Oh, and how they change!

The narrative design and gameplay in Papers, Please are at the zeitgeist of an epoch-defining trend: mass migration and increased border enforcement. The decade following Papers, Please has had a whirlwind of immigration policy changes and practices worldwide. Just this year alone in the United States, we witnessed the end of Title 42 (pandemic-era immigration restrictions in the United States), a backlog of over one million asylum applications as of May 2023, overworked staff, and a sharp increase in student visa denials. Globally, people are leaving their homes. Spurred by large-scale armed conflicts, economic devastation, climate change, and the hope of opportunity, rationally, people migrate. We haven’t seen migration at this scale since the Second World War. Imagine being the inspector in Papers, Please and processing immigration claims by people on the Southern border of the United States or in Eastern Europe processing Ukrainian refugees at the Polish border.

Pope spoke about players telling him “…that the game reflected their experience immigrating from one place to another and the complications they faced. All horror stories, basically.” The bureaucratic work players are tasked with in Papers, Please is not dissimilar from that performed by Customs and Border Patrol, specifically before the creation of the Asylum Corps (a cadre of officers trained to review and adjudicate domestic refugee processing) in 1991. In its inception, the Asylum Corps was predominantly composed of individuals trained in immigration law. Before the Asylum Corps’ creation, it was the job of border inspectors to adjudicate asylum claims on top of their other duties. Asylees are the ones who would fall under the purview of the inspector in Papers, Please, as these individuals have to present themselves at a legal port of entry and state their claim to asylum.

Papers, Please gamifies the process of policing migration. Yet, one key distinction between migration processing in Papers, Please, and our contemporary world is how borders now operate as extended zones, often outside the specific national border itself. Burton shared his insights on this matter. “Borders as a larger expanded geographical defuse area is a super recent phenomenon,” he says. “We are talking about 15 to 20 years ago. For example, the U.S. Customs and Board Agency starts functioning as far south as Peru. The U.S. border really starts at the Guatemala-Mexico border. The border with Europe starts in Mali, in Niger, in Burkina Faso, and moves through to the Mediterranean by the time you need border officials.”

As previously noted by Pope, this and other trends and procedures relating to migration are not covered by Papers, Please. The game offers an overly simplified version of migration control, both to the game’s benefit and to its detriment. It is not a complete or accurate depiction of the lived experiences of migrants and asylum-seekers. Also, deeply coloring its perspectives are older and now largely defunct ways in which destination countries (places where immigrants would like to ultimately reside) process migrants at their borders.

Burton sees Papers, Please as “…almost like a replay of the 20th century’s ideas about borders. Which I think are shaped by, and the policy imperatives come by, the testimonies of all the people in Europe after the Second World War of the idea of being at the border and not being allowed in. Well, in the present day, you are not even going to get to the border. You already go through a period of scrutiny [before arriving at the country of destination] […] I had a pretty unique experience where I was the guy saying ‘no,’ but usually as part of an extremely diffuse process. I also think that it’s interesting that Papers, Please is set in an environment in what I guess you’ll call ‘real existing socialism.’ It’s clearly supposed to be in a Romania or Albania kind of analog. In a hyper isolated kind of independent eastern European communist country.” These kinds of “isolated” countries are rarer today.

Papers, Please is a towering achievement, regardless of how its mechnaics and view of migration differ from reality. Few games are as bold and interweave narrative and gameplay so succinctly. The game’s themes are malleable to the specific societal context that the player brings. Routinely, it’s used by academics in classrooms and continues to captivate players looking for more than just a few hours of entertainment.

A decade after its release, Papers, Please stands as a singular vision that is myopic, bleak, and unflinching. It is also riveting. The game is an example of Pope’s strong belief in the power of interactive media to build empathy. According to Pope, “If Papers, Please can raise awareness about these issues, then I’m very happy. I think a fundamental problem with understanding migration is that the topic is so distant from most people’s comfortable daily experience. Having the situations and challenges right up in your face, subject to your choices can hopefully encourage more empathetic ways to think about them.”

This article originally appeared in Issue 361 of Game Informer