Like humans and other complex multicellular organisms, single-celled bacteria can fall ill and fight off viral infections. A bacterial virus is caused by a bacteriophage, or, more simply, phage, which is one of the most ubiquitous life forms on earth. Phages and bacteria are engaged in a constant battle, the virus attempting to circumvent the bacteria’s defenses, and the bacteria racing to find new ways to protect itself.

These anti-phage defense systems are carefully controlled, and prudently managed — dormant, but always poised to strike.

New open-access research recently published in Nature from the Laub Lab in the Department of Biology at MIT has characterized an anti-phage defense system in bacteria, CmdTAC. CmdTAC prevents viral infection by altering the single-stranded genetic code used to produce proteins, messenger RNA.

This defense system detects phage infection at a stage when the viral phage has already commandeered the host’s machinery for its own purposes. In the face of annihilation, the ill-fated bacterium activates a defense system that will halt translation, preventing the creation of new proteins and aborting the infection — but dooming itself in the process.

“When bacteria are in a group, they’re kind of like a multicellular organism that is not connected to one another. It’s an evolutionarily beneficial strategy for one cell to kill itself to save another identical cell,” says Christopher Vassallo, a postdoc and co-author of the study. “You could say it’s like self-sacrifice: One cell dies to protect the other cells.”

The enzyme responsible for altering the mRNA is called an ADP-ribosyltransferase. Researchers have characterized hundreds of these enzymes — although a few are known to target DNA or RNA, all but a handful target proteins. This is the first time these enzymes have been characterized targeting mRNA within cells.

Expanding understanding of anti-phage defense

Co-first author and graduate student Christopher Doering notes that it is only within the last decade or so that researchers have begun to appreciate the breadth of diversity and complexity of anti-phage defense systems. For example, CRISPR gene editing, a technique used in everything from medicine to agriculture, is rooted in research on the bacterial CRISPR-Cas9 anti-phage defense system.

CmdTAC is a subset of a widespread anti-phage defense mechanism called a toxin-antitoxin system. A TA system is just that: a toxin capable of killing or altering the cell’s processes rendered inert by an associated antitoxin.

Although these TA systems can be identified — if the toxin is expressed by itself, it kills or inhibits the growth of the cell; if the toxin and antitoxin are expressed together, the toxin is neutralized — characterizing the cascade of circumstances that activates these systems requires extensive effort. In recent years, however, many TA systems have been shown to serve as anti-phage defense.

Two general questions need to be answered to understand a viral defense system: How do bacteria detect an infection, and how do they respond?

Detecting infection

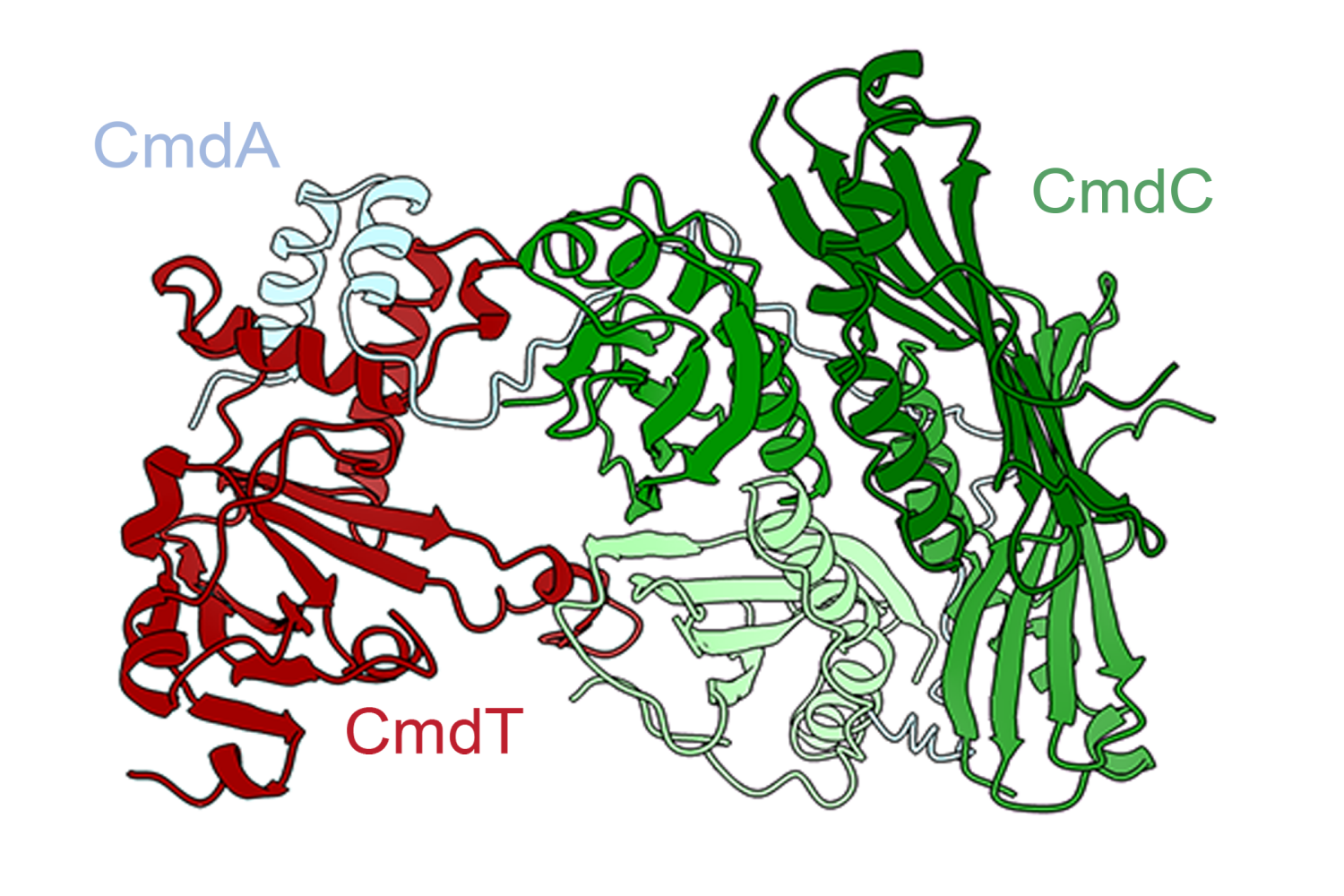

CmdTAC is a TA system with an additional element, and the three components generally exist in a stable complex: the toxic CmdT, the antitoxin CmdA, and an additional component called a chaperone, CmdC.

If the phage’s protective capsid protein is present, CmdC disassociates from CmdT and CmdA and interacts with the phage capsid protein instead. In the model outlined in the paper, the chaperone CmdC is, therefore, the sensor of the system, responsible for recognizing when an infection is occurring. Structural proteins, such as the capsid that protects the phage genome, are a common trigger because they’re abundant and essential to the phage.

The uncoupling of CmdC exposes the neutralizing antitoxin CmdA to be degraded, which releases the toxin CmdT to do its lethal work.

Toxicity on the loose

The researchers were guided by computational tools, so they knew that CmdT was likely an ADP-ribosyltransferase due to its similarities to other such enzymes. As the name suggests, the enzyme transfers an ADP ribose onto its target.

To determine if CmdT interacted with any sequences or positions in particular, they tested a mix of short sequences of single-stranded RNA. RNA has four bases: A, U, G, and C, and the evidence points to the enzyme recognizing GA sequences.

The CmdT modification of GA sequences in mRNA blocks their translation. The cessation of creating new proteins aborts the infection, preventing the phage from spreading beyond the host to infect other bacteria.

“Not only is it a new type of bacterial immune system, but the enzyme involved does something that’s never been seen before: the ADP-ribsolyation of mRNA,” Vassallo says.

Although the paper outlines the broad strokes of the anti-phage defense system, it’s unclear how CmdC interacts with the capsid protein, and how the chemical modification of GA sequences prevents translation.

Beyond bacteria

More broadly, exploring anti-phage defense aligns with the Laub Lab’s overall goal of understanding how bacteria function and evolve, but these results may have broader implications beyond bacteria.

Senior author Michael Laub, Salvador E. Luria Professor and Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator, says the ADP-ribosyltransferase has homologs in eukaryotes, including human cells. They are not well studied, and not among the Laub Lab’s research topics, but they are known to be up-regulated in response to viral infection.

“There are so many different — and cool — mechanisms by which organisms defend themselves against viral infection,” Laub says. “The notion that there may be some commonality between how bacteria defend themselves and how humans defend themselves is a tantalizing possibility.”