It’s not the kind of security discovery that happens often. A previously unknown hacker group used a novel backdoor, top-notch trade craft, and software engineering to create an espionage botnet that was largely invisible in many victim networks.

The group, which security firm Mandiant is calling UNC3524, has spent the past 18 months burrowing into victims’ networks with unusual stealth. In cases where the group is ejected, it wastes no time reinfecting the victim environment and picking up where things left off. There are many keys to its stealth, including:

- the use of a unique backdoor Mandiant calls Quietexit, which runs on load balancers, wireless access point controllers, and other types of IoT devices that don’t support antivirus or endpoint detection. This makes detection through traditional means difficult

- customized versions of the backdoor that use file names and creation dates that are similar to legitimate files used on a specific infected device

- a live-off-the-land approach that favors common Windows programming interfaces and tools over custom code with the goal of leaving as light a footprint as possible

- an unusual way a second-stage backdoor connects to attacker-controlled infrastructure by, in essence, acting as a TLS-encrypted server that proxies data through the SOCKS protocol

A tunneling fetish with SOCKS

In a post, Mandiant researchers Doug Bienstock, Melissa Derr, Josh Madeley, Tyler McLellan, and Chris Gardner wrote:

Throughout their operations, the threat actor demonstrated sophisticated operational security that we see only a small number of threat actors demonstrate. The threat actor evaded detection by operating from devices in the victim environment’s blind spots, including servers running uncommon versions of Linux and network appliances running opaque OSes. These devices and appliances were running versions of operating systems that were unsupported by agent-based security tools, and often had an expected level of network traffic that allowed the attackers to blend in. The threat actor’s use of the QUIETEXIT tunneler allowed them to largely live off the land, without the need to bring in additional tools, further reducing the opportunity for detection. This allowed UNC3524 to remain undetected in victim environments for, in some cases, upwards of 18 months.

The SOCKS tunnel allowed the hackers to effectively connect their control servers into a victim’s network where they could then execute tools without leaving traces on any of the victim computers.

A secondary backdoor provided an alternate means of access to infected networks. It was based on a version of the legitimate reGeorg webshell that had been heavily obfuscated to make detection harder. The threat actor used it in the event the primary backdoor stopped working. The researchers explained:

Once inside the victim environment, the threat actor spent time to identify web servers in the victim environment and ensure they found one that was Internet accessible before copying REGEORG to it. They also took care to name the file so that it blended in with the application running on the compromised server. Mandiant also observed instances where UNC3452 used timestomping [referring to a tool available here for deleting or modifying timestamp-related information on files] to alter the Standard Information timestamps of the REGEORG web shell to match other files in the same directory.

One of the ways the hackers maintain a low profile is by favoring standard Windows protocols over malware to move laterally. To move to systems of interest, UNC3524 used a customized version of WMIEXEC, a tool that uses Windows Management Instrumentation to establish a shell on the remote system.

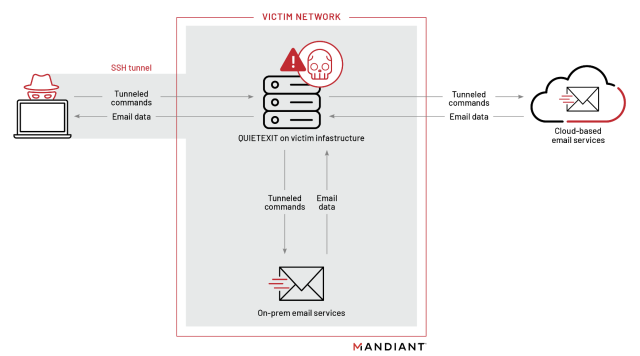

Eventually, Quietexit executes its final objective: accessing email accounts of executives and IT personnel in hopes of obtaining documents related to things like corporate development, mergers and acquisitions, and large financial transactions.

“Once UNC3524 successfully obtained privileged credentials to the victim’s mail environment, they began making Exchange Web Services (EWS) API requests to either the on-premises Microsoft Exchange or Microsoft 365 Exchange Online environment,” the Mandiant researchers wrote. “In each of the UNC3524 victim environments, the threat actor would target a subset of mailboxes….”

Not your typical APT

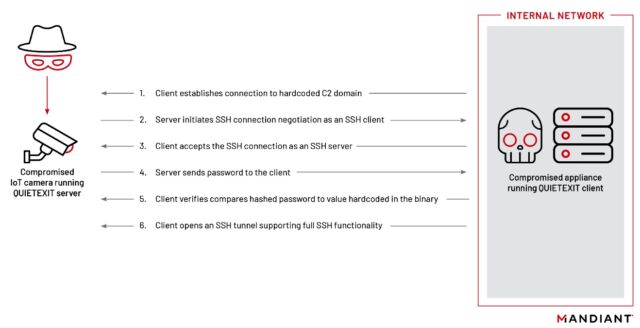

The Quietexit command-and-control infrastructure is among the most intricate in recent memory. In many cases, the attacker-operated servers to which infected machines connected were legacy conference room camera systems sold by Lifesize or, in at least one case, D-Link, which had been infected with the server component of Quietexit. This diagram shows how a Windows device infected with the Quietexit client version connected to a camera, router, or other IoT device that had been turned into a command-and-control server:

Also notable is the extra effort the threat actor put into obtaining control-server domain names that were chosen based on the specifics of its network environment.

“We observed UNC3524 use C2 domains that intended to blend in with legitimate traffic originating from the infected appliances,” the researchers explained. “Using the example of an infected load balancer, the C2 domains contained strings that could plausibly relate to the device vendor and branded operating system name. This level of planning demonstrates that UNC3524 understands incident response processes and tried to make their C2 traffic appear as legitimate to anyone that might scroll through DNS or session logs.”

The tactics and methodologies of UNC3524 overlap with those of the two Russian state hacker groups known as APT28, or Fancy Bear, and APT29, or Cozy Bear. Quietexit includes a technique that uses multiple credentials to move laterally that was also used by Fancy Bear during the SolarWinds breach campaign. Automated password spraying using Kubernetes, Exchange Exploitation, and REGEORG are things Cozy Bear has left behind in past hacks. Ultimately, Mandiant was unable to conclusively link UNC3524 to either group, or any other known one as well.

Unpacking this threat group is difficult. From outward appearances, their focus on corporate transactions suggests a financial interest. But UNC3524’s high-caliber tradecraft, proficiency with sophisticated IoT botnets, and ability to remain undetected for so long suggests something more.

“Part of the group’s success at achieving such a long dwell time can be credited to their choice to install backdoors on appliances within victim environments that do not support security tools, such as antivirus or endpoint protection,” the researchers wrote. “The high level of operational security, low malware footprint, adept evasive skills, and a large Internet of Things (IoT) device botnet set this group apart and emphasize the ‘advanced’ in Advanced Persistent Threat.”