As a teenager living in a small village in what was then Yugoslavia, Admir Masic witnessed the collapse of his home country and the outbreak of the Bosnian war. When his childhood home was destroyed by a tank, his family was forced to flee the violence, leaving their remaining possessions to enter a refugee camp in northern Croatia.

It was in Croatia that Masic found what he calls his “magic.”

“Chemistry really forcefully entered my life,” recalls Masic, who is now an associate professor in MIT’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. “I’d leave school to go back to my refugee camp, and you could either play ping-pong or do chemistry homework, so I did a lot of homework, and I began to focus on the subject.”

Masic has never let go of his magic. Long after chemistry led him out of Croatia, he’s come to understand that the past holds crucial lessons for building a better future. That’s why he started the MIT Refugee Action Hub (now MIT Emerging Talent) to provide educational opportunities to students displaced by war. It’s also what led him to study ancient materials, whose secrets he believes have potential to solve some of the modern world’s most pressing problems.

“We’re leading this concept of paleo-inspired design: that there are some ideas behind these ancient materials that are useful today,” Masic says. “We should think of these materials as a source of valuable information that we can try to translate to today. These concepts have the potential to revolutionize how we think about these materials.”

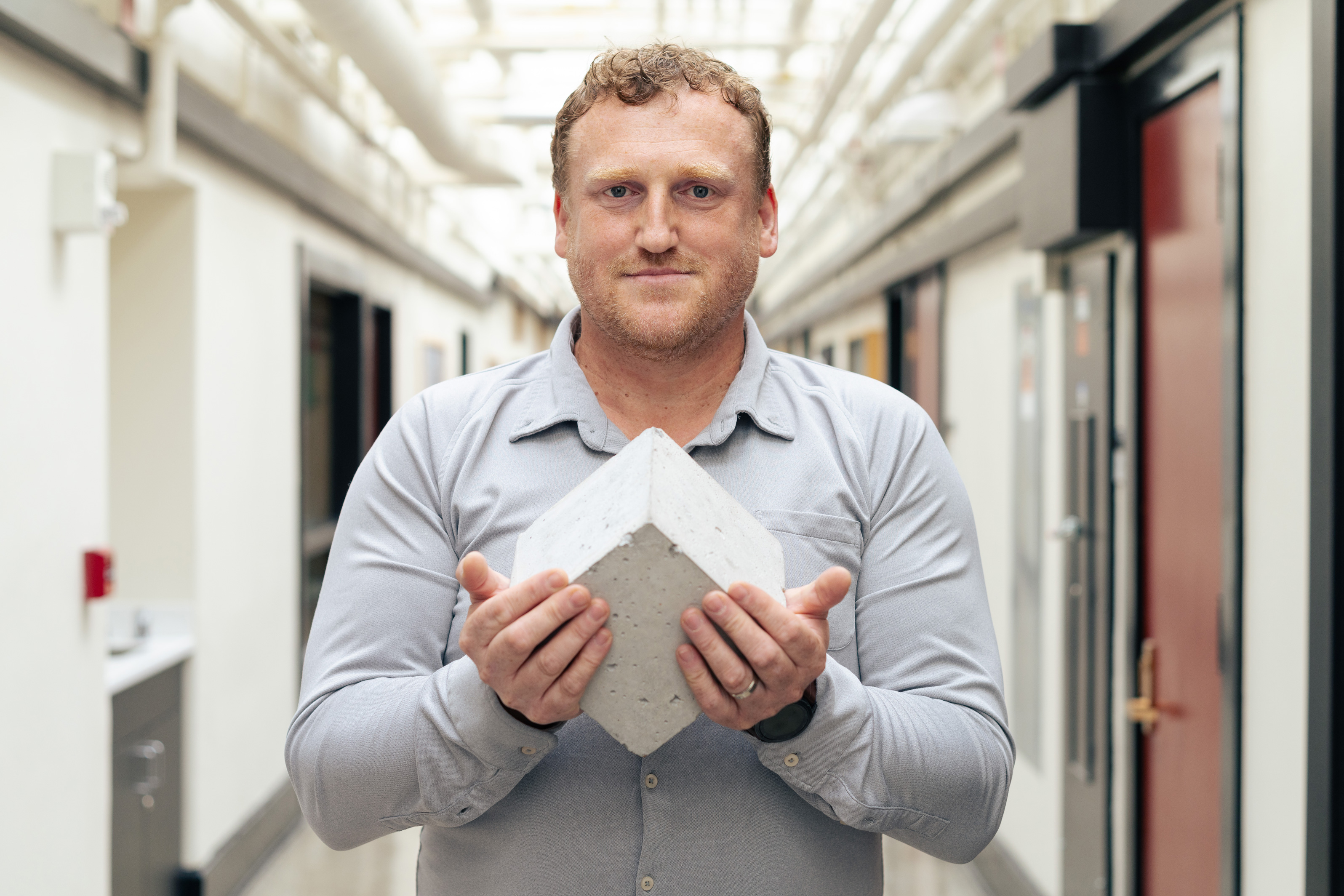

One key research focus for Masic is cement. His lab is working on ways to transform the ubiquitous material into a carbon sink, a medium for energy storage, and more. Part of that work involves studying ancient Roman concrete, whose self-healing properties he has helped to illuminate.

At the core of each of Masic’s research endeavors is a desire to translate a better understanding of materials into improvements in how we make things around the world.

“Roman concrete to me is fascinating: It’s still standing after all this time and constantly repairing,” Masic says. “It’s clear there’s something special about this material, so what is it? Can we translate part of it into modern analogues? That’s what I love about MIT. We are put in a position to do cutting-edge research and then quickly translate that research into the real world. Impact for me is everything.”

Finding a purpose

Masic’s family fled to Croatia in 1992, just as he was set to begin high school. Despite excellent grades, Masic was told Bosnian refugees couldn’t enroll in the local school. It was only after a school psychologist advocated for Masic that he was allowed to sit in on classes as a nonmatriculating student.

Masic did his best to be a ghost in the back of classrooms, silently absorbing everything he could. But in one subject he stood out. Within six months of joining the school, in January of 1993, a teacher suggested Masic compete in a local chemistry competition.

“It was kind of the Olympiads of chemistry, and I won,” Masic recalls. “I literally floated onto the stage. It was this ‘Aha’ moment. I thought, ‘Oh my god, I’m good at chemistry!’”

In 1994, Masic’s parents immigrated to Germany in search of a better life, but he decided to stay behind to finish high school, moving into a friend’s basement and receiving food and support from local families as well as a group of volunteers from Italy.

“I just knew I had to stay,” Masic says. “With all the highs and lows of life to that point, I knew I had this talent and I had to make the most of it. I realized early on that knowledge was the one thing no one could take away from me.”

Masic continued competing in chemistry competitions — and continued winning. Eventually, after a change to a national law, the high school he was attending agreed to give him a diploma. With the help of the Italian volunteers, he moved to Italy to attend the University of Turin, where he entered a five-year joint program that earned him a master’s degree in inorganic chemistry. Masic stayed at the university for his PhD, where he studied parchment, a writing material that’s been used for centuries to record some of humanity’s most sacred texts.

With a classmate, Masic started a company that helped restore ancient documents. The work took him to Germany to work on a project studying the Dead Sea Scrolls, a set of manuscripts that date as far back as the third century BCE. In 2008, Masic joined the Max Planck Institute in Germany, where he also began to work with biological materials, studying water’s interaction with collagen at the nanoscale.

Through that work, Masic became an expert in Raman spectroscopy, a type of chemical imaging that uses lasers to record the vibrations of molecules without leaving a trace, which he still uses to characterize materials.

“Raman became a tool for me to contribute in the field of biological materials and bioinspired materials,” Masic says. “At the same time, I became the ‘Raman guy.’ It was a remarkable period for me professionally, as these tools provided unparalleled information and I published a lot of papers.”

After seven years at Max Planck, Masic joined the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE) at MIT.

“At MIT, I felt I could truly be myself and define the research I wanted to do,” Masic says. “Especially in CEE, I could connect my work in heritage science and this tool, Raman spectroscopy, to tackle our society’s big challenges.”

From labs to the world

Raman spectroscopy is a relatively new approach to studying cement, a material that contributes significantly to carbon dioxide emissions worldwide. At MIT, Masic has explored ways cement could be used to store carbon dioxide and act as an energy-storing supercapacitor. He has also solved ancient mysteries about the lasting strength of ancient Roman concrete, with lessons for the $400 billion cement industry today.

“We really don’t think we should replace ordinary Portland cement completely, because it’s an extraordinary material that everyone knows how to work with, and industry produces so much of it. We need to introduce new functionalities into our concrete that will compensate for cement’s sustainability issues through avoided emissions,” Masic explains. “The concept we call ‘multifunctional concrete’ was inspired by our work with biological materials. Bones, for instance, sacrifice mechanical performance to be able to do things like self-healing and energy storage. That’s how you should imagine construction over next 10 years or 20 years. There could be concrete columns and walls that primarily offer support but also do things like store energy and continuously repair themselves.”

Masic’s work across academia and industry allows him to apply his multifunctional concrete research at scale. He serves as a co-director of the MIT ec3 hub, a principal investigator within MIT Concrete Sustainability Hub, and a co-founder and advisor at the technology development company DMAT.

“It’s great to be at the forefront of sustainability but also to be directly interacting with key industry players that can change the world,” Masic says. “What I appreciate about MIT is how you can engage in fundamental science and engineering while also translating that work into practical applications. The CSHub and ec3 hub are great examples of this. Industry is eager for us to develop solutions that they can help support.”

And Masic will never forget where he came from. He now lives in Somerville, Massachusetts, with his wife Emina, a fellow former refugee, and their son, Benjamin, and the family shares a deep commitment to supporting displaced and underserved communities. Seven years ago, Masic founded the MIT Refugee Action Hub (ReACT), which provides computer and data science education programs for refugees and displaced communities. Today thousands of refugees apply to the program every year, and graduates have gone on to successful careers at places like Microsoft and Meta. The ReACT program was absorbed by MIT’s Emerging Talent program earlier this year to further its reach.

“It’s really a life-changing experience for them,” Masic says. “It’s an amazing opportunity for MIT to nurture talented refugees around the world through this simple certification program. The more people we can involve, the more impact we will have on the lives of these truly underserved communities.”