This blog post is authored by Shayne Longpre, Sayash Kapoor, Kevin Klyman, Ashwin Ramaswami, Rishi Bommasani, Arvind Narayanan, Percy Liang, and Peter Henderson. The paper has 23 authors and is available here.

Today, we are releasing an open letter encouraging AI companies to provide legal and technical protections for good-faith research on their AI models. The letter focuses on the importance of independent evaluations of proprietary generative AI models, particularly those with millions of users. In an accompanying paper, we discuss existing challenges to independent research and how a more equitable, transparent, and accountable researcher ecosystem could be developed.

The letter has been signed by researchers, practitioners, and advocates across disciplines, and is open for signatures.

Read and sign the open letter here. Read the paper here.

AI companies, academic researchers, and civil society agree that generative AI models pose acute risks: independent risk assessment is an essential mechanism for providing accountability. Nevertheless, barriers exist that inhibit the independent evaluation of many AI models.

Independent researchers often evaluate and “red team” AI models to measure a variety of different risks. In this work, we focus on post-release evaluation of models (or APIs) by external researchers beyond the model developer. In is also referred to as algorithmic audits by third-parties. Some companies also conduct red teaming before their models are released both internally and with experts they select.

While many types of testing are critical, independent evaluation of AI models that are already deployed is widely regarded as essential for ensuring safety, security, and trust. Independent red-teaming research of AI models has uncovered vulnerabilities related to low resource languages, bypassing safety measure, and a wide range of jailbreaks. These evaluations investigate a broad set of often unanticipated model flaws, related to misuse, bias, copyright, and other issues.

Despite the need for independent evaluation, conducting research related to these vulnerabilities is often legally prohibited by the terms of service for popular AI models, including those of OpenAI, Google, Anthropic, Inflection, Meta, and Midjourney.

While these terms are intended as a deterrent against malicious actors, they also inadvertently restrict AI safety and trustworthiness research—companies forbid the research and may enforce their policies with account suspensions (as an example, see Anthropic’s acceptable use policy). While companies enforce these restrictions to varying degrees, the terms can disincentivize good-faith research by granting developers the right to terminate researchers’ accounts or even take legal action against them. Often, there is limited transparency into the enforcement policy, and no formal mechanism for justification or appeal of account suspensions. Even aside from the legal deterrent, the risk of losing account access by itself, may dissuade researchers who depend on these accounts for other critical types of AI research.

Evaluating the risks of models that are already deployed and have millions of users is essential as they pose immediate risks. However, only a relatively small group of researchers selected by companies have legal authorization to do so.

AI developers have engaged to differing degrees with external red teamers and evaluators. For example, OpenAI, Google, and Meta have bug bounties (that provide monetary rewards to people to report security vulnerabilities) and even legal protections for security research. Still, companies like Meta and Anthropic currently “reserve final and sole discretion for whether you are acting in good faith and in accordance with this Policy,” which could deter good-faith security research. These legal protections extend only to traditional security issues like unauthorized account access and do not include broader safety and trustworthiness research.

Cohere and OpenAI are exceptions, though some ambiguity remains as to the scope of protected activities: Cohere allows “intentional stress testing of the API and adversarial attacks” provided appropriate vulnerability disclosure (without explicit legal promises), and OpenAI expanded its safe harbor to include “model vulnerability research” and “academic model safety research” in response to an early draft of our proposal.

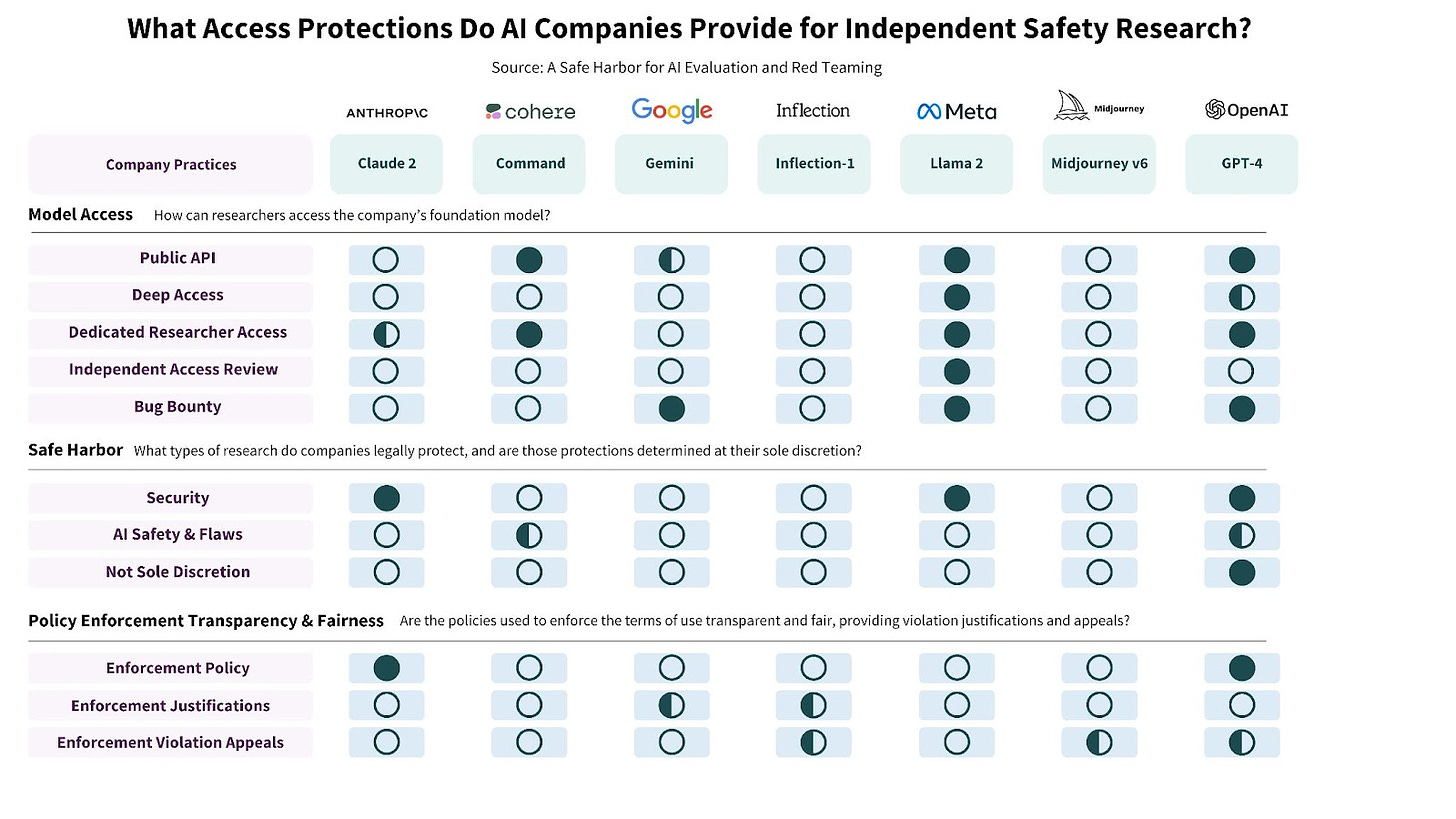

In the table below, we document gaps in the policies of leading AI companies. These gaps force well-intentioned researchers to either wait for approval from unresponsive researcher access programs, or risk violating company policy and losing access to their accounts.

We believe that a pair of voluntary commitments could significantly improve participation, access, and incentives for public interest research into AI safety. The two commitments are: a legal safe harbor, protecting good-faith, public interest evaluation research provided it is conducted in accordance with well-established security vulnerability disclosure practices, and a technical safe harbor, protecting this evaluation research from account termination. Both safe harbors should be scoped to include research activities that uncover any system flaws, including all undesirable generations currently prohibited by a company’s terms of service.

As others have argued, this would not inhibit existing enforcement against malicious misuse, as protections are entirely contingent on abiding by the law and strict vulnerability disclosure policies, determined ex-post. The legal safe harbor, similar to a proposal by the Knight First Amendment Institute for a safe harbor for research on social media platforms, would safeguard certain research from some amount of legal liability, mitigating the deterrent of strict terms of service. The technical safe harbor would limit the practical barriers to safety research from companies’ enforcement of their terms by clarifying that researchers will not be penalized.

A legal safe harbor could provide assurances that AI companies will not sue researchers if their actions were taken for research purposes. In the US legal regime, this would impact companies’ use of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) and Section 1201 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA). These risks are not theoretical; security researchers have been targeted under the CFAA, and DMCA Section 1201 hampered security research to the extent that researchers requested and won an exemption from the law for this purpose. Already, in the context of generative AI, OpenAI has attempted to dismiss the NYTimes v OpenAI lawsuit on the allegation that NYTimes research into the model constituted hacking.

These protections apply only to researchers who abide by companies’ vulnerability disclosure policies, to the extent researchers can subsequently justify their actions in court. Research that is already illegal or does not take reasonable steps for responsible disclosure would not succeed in claiming those protections in an ex-post investigation. The Algorithmic Justice League has also proposed legal protections for third-party auditors of proprietary systems.

Legal safe harbors alone do not prevent account suspensions or other technical enforcement actions, such as rate limiting. These technical obstacles can also impede independent safety evaluations. We refer to the protection of research against these technical enforcement measures as a technical safe harbor. Without sufficient technical protections for public interest research, an asymmetry can develop between malicious and non-malicious actors, since non-malicious actors are discouraged from investigating vulnerabilities exploited by malicious actors.

We propose companies offer some path to eliminate these technical barriers for good-faith research, even when it can be critical of companies’ models. This would include more equitable opportunities for researcher access and guarantees that those opportunities will not be foreclosed for researchers who adhere to companies’ vulnerability disclosure policies. One way to do this is scale up researcher access programs and provide impartial review of applications for these programs. The challenge with implementing a technical safe harbor is distinguishing between legitimate research and malicious actors. An exemption to strict enforcement of companies’ policies may need to be reviewed in advance, or at least when an unfair account suspension occurs. However, we believe this problem is tractable with participation from independent third parties.

The need for independent AI evaluation has garnered significant support from academics, journalists, and civil society. We identify legal and technical safe harbors as minimum fundamental protections for ensuring independent safety and trustworthiness research. They would significantly improve ecosystem norms, and drive more inclusive and unimpeded community efforts to tackle the risks of generative AI.

Further reading

Our work is inspired by and builds on several proposals in past literature:

Policy proposals directly related to protecting types of AI research from liability from the DMCA or CFAA:

-

The Hacking Policy Council proposes that governments “clarify and extend legal protections for independent AI red teaming,” similar to our voluntary legal safe harbor proposal.

-

A petition for a new exemption to the DMCA has been filed to facilitate research on AI bias and promote transparency in AI.

Independent algorithmic audits and their design:

Algorithmic bug bounties, safe harbors, and their design

Other related proposals and red teaming work: