A recent study from the University of California, Merced, has shed light on a concerning trend: our tendency to place excessive trust in AI systems, even in life-or-death situations. As AI continues to permeate various aspects of our society, from smartphone assistants to complex decision-support systems,…

Altered AI Review: Using AI for Real-Time Voice Morphing

As a content creator or media professional, delivering diverse, high-quality voice performances can be incredibly challenging. Whether juggling multiple roles or managing tight budgets, the cost of hiring voice actors can weigh you down. I recently came across Altered AI, an innovative platform that offers incredible…

Here’s What to Know About Ilya Sutskever’s $1B Startup SSI

In a bold move that has caught the attention of the entire AI community, Safe Superintelligence (SSI) has burst onto the scene with a staggering $1 billion in funding. First reported by Reuters, this three-month-old startup, co-founded by former OpenAI chief scientist Ilya Sutskever, has quickly…

Study assesses seizure risk from stimulating the thalamus

The idea of electrically stimulating a brain region called the central thalamus has gained traction among researchers and clinicians because it can help arouse subjects from unconscious states induced by traumatic brain injury or anesthesia, and can boost cognition and performance in awake animals. But the method, called CT-DBS, can have a side effect: seizures. A new study by researchers at MIT and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) who were testing the method in awake mice quantifies the probability of seizures at different stimulation currents and cautions that they sometimes occurred even at low levels.

“Understanding production and prevalence of this type of seizure activity is important because brain stimulation-based therapies are becoming more widely used,” says co-senior author Emery N. Brown, Edward Hood Taplin Professor of Medical Engineering and Computational Neuroscience in The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, the Institute for Medical Engineering and Science, the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, and the Center for Brains Minds and Machines (CBMM) at MIT.

In the brain, the seizures associated with CT-DBS occur as “electrographic seizures,” which are bursts of voltage among neurons across a broad spectrum of frequencies. Behaviorally, they manifest as “absence seizures” in which the subject appears to take on a blank stare and freezes for about 10-20 seconds.

In their study, the researchers were hoping to determine a CT-DBS stimulation current — in a clinically relevant range of under 200 microamps — below which seizures could be reliably avoided.

In search of that ideal current, they developed a protocol of starting brief bouts of CT-DBS at 1 microamp and then incrementally ramping the current up to 200 microamps until they found a threshold where an electrographic seizure occurred. Once they found that threshold, then they tested a longer bout of stimulation at the next lowest current level in hopes that an electrographic seizure wouldn’t occur. They did this for a variety of different stimulation frequencies. To their surprise, electrographic seizures still occurred 2.2 percent of the time during those longer stimulation trials (i.e. 22 times out of 996 tests) and in 10 out of 12 mice. At just 20 microamps, mice still experienced seizures in three out of 244 tests, a 1.2 percent rate.

“This is something that we needed to report because this was really surprising,” says co-lead author Francisco Flores, a research affiliate in The Picower Institute and CBMM, and an instructor in anesthesiology at MGH, where Brown is also an anesthesiologist. Isabella Dalla Betta, a technical associate in The Picower Institute, co-led the study published in Brain Stimulation.

Stimulation frequency didn’t matter for seizure risk but the rate of electrographic seizures increased as the current level increased. For instance, it happened in 5 out of 190 tests at 50 microamps, and two out of 65 tests at 100 microamps. The researchers also found that when an electrographic seizure occurred, it did so more quickly at higher currents than at lower levels. Finally, they also saw that seizures happened more quickly if they stimulated the thalamus on both sides of the brain, versus just one side. Some mice exhibited behaviors similar to absence seizure, though others became hyperactive.

It is not clear why some mice experienced electrographic seizures at just 20 microamps while two mice did not experience the seizures even at 200. Flores speculated that there may be different brain states that change the predisposition to seizures amid stimulation of the thalamus. Notably, seizures are not typically observed in humans who receive CT-DBS while in a minimally conscious state after a traumatic brain injury or in animals who are under anesthesia. Flores said the next stage of the research would aim to discern what the relevant brain states may be.

In the meantime, the study authors wrote, “EEG should be closely monitored for electrographic seizures when performing CT-DBS, especially in awake subjects.”

The paper’s co-senior author is Matt Wilson, Sherman Fairchild Professor in The Picower Institute, CBMM, and the departments of Biology and Brain and Cognitive Sciences. In addition to Dalla Betta, Flores, Brown and Wilson, the study’s other authors are John Tauber, David Schreier, and Emily Stephen.

Support for the research came from The JPB Foundation, The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory; George J. Elbaum ’59, SM ’63, PhD ’67, Mimi Jensen, Diane B. Greene SM ’78, Mendel Rosenblum, Bill Swanson, annual donors to the Anesthesia Initiative Fund; and the National Institutes of Health.

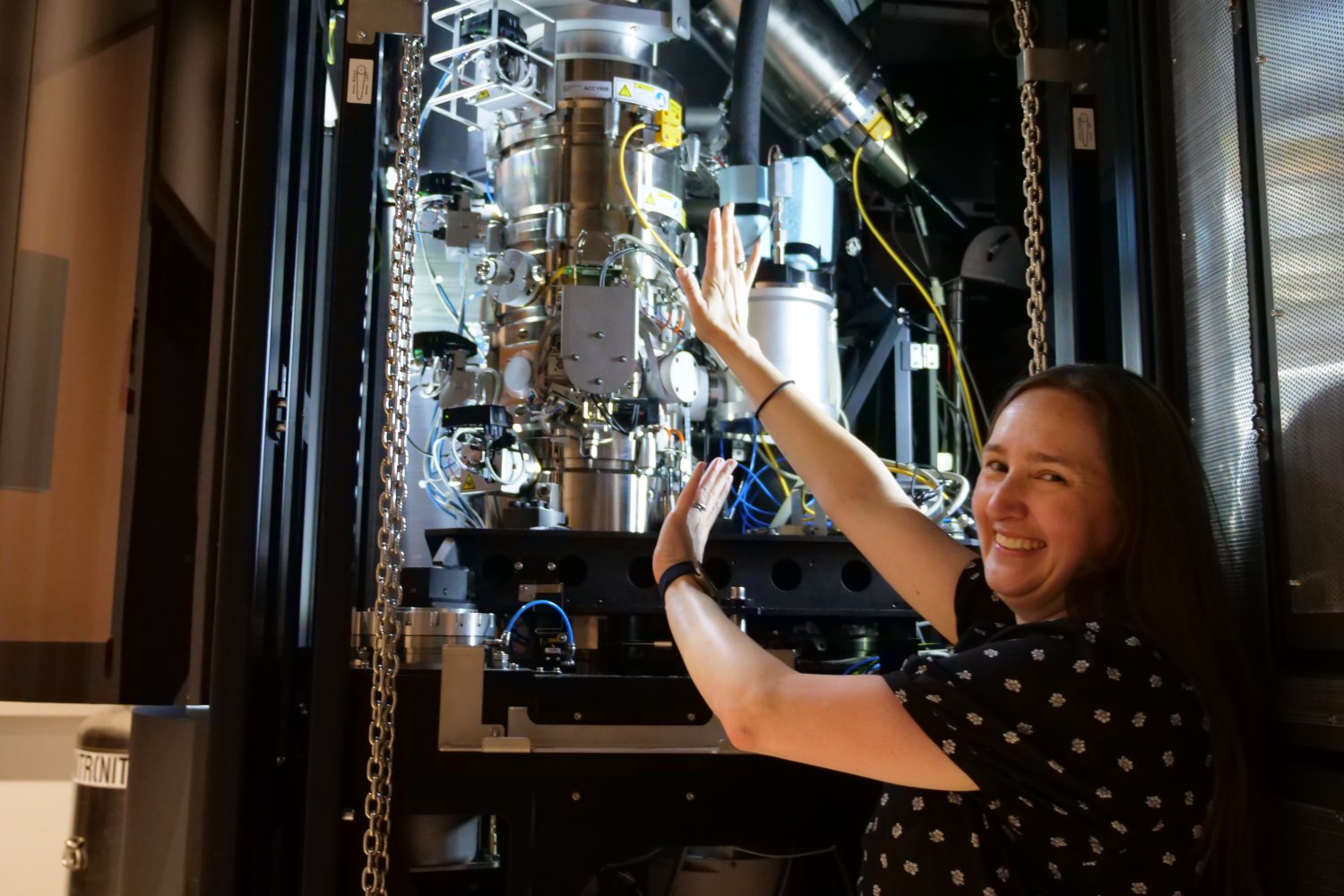

No detail too small

Sarah Sterling, director of the Cryo-Electron Microscopy, or Cryo-EM, core facility, often compares her job to running a small business. Each day brings a unique set of jobs ranging from administrative duties and managing facility users to balancing budgets and maintaining equipment.

Although one could easily be overwhelmed by the seemingly never-ending to-do list, Sterling finds a great deal of joy in wearing so many different hats. One of her most essential tasks involves clear communication with users when the delicate instruments in the facility are unusable because of routine maintenance and repairs.

“Better planning allows for better science,” Sterling says. “Luckily, I’m very comfortable with building and fixing things. Let’s troubleshoot. Let’s take it apart. Let’s put it back together.”

Out of all her duties as a core facility director, she most looks forward to the opportunities to teach, especially helping students develop research projects.

“Undergraduate or early-stage graduate students ask the best questions,” she says. “They’re so curious about the tiny details, and they’re always ready to hit the ground running on their projects.”

A non-linear scientific journey

When Sterling enrolled in Russell Sage College, a women’s college in New York, she was planning to pursue a career as a physical therapist. However, she quickly realized she loved her chemistry classes more than her other subjects. She graduated with a bachelor of science degree in chemistry and immediately enrolled in a master’s degree program in chemical engineering at the University of Maine.

Sterling was convinced to continue her studies at the University of Maine with a dual PhD in chemical engineering and biomedical sciences. That decision required the daunting process of taking two sets of core courses and completing a qualifying exam in each field.

“I wouldn’t recommend doing that,” she says with a laugh. “To celebrate after finishing that intense experience, I took a year off to figure out what came next.”

Sterling chose to do a postdoc in the lab of Eva Nogales, a structural biology professor at the University of California at Berkeley. Nogales was looking for a scientist with experience working with lipids, a class of molecules that Sterling had studied extensively in graduate school.

At the time Sterling joined, the Nogales Lab was at the forefront of implementing an exciting structural biology approach: cryo-EM.

“When I was interviewing, I’d never even seen the type of microscope required for cryo-EM, let alone performed any experiments,” Sterling says. “But I remember thinking ‘I’m sure I can figure this out.’”

Cryo-EM is a technique that allows researchers to determine the three-dimensional shape, or structure, of the macromolecules that make up cells. A researcher can take a sample of their macromolecule of choice, suspend it in a liquid solution, and rapidly freeze it onto a grid to capture the macromolecules in random positions — the “cryo” part of the name. Powerful electron microscopes then collect images of the macromolecule — the EM part of cryo-EM.

The two-dimensional images of the macromolecules from different angles can be combined to produce a three-dimensional structure. Structural information like this can reveal the macromolecule’s function inside cells or inform how it differs in a disease state. The rapidly expanding use of cryo-EM has unlocked so many mechanistic insights that the researchers who developed the technology were awarded the 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

The MIT.nano facility opened its doors in 2018. The open-access, state-of-the-art facility now has more than 160 tools and more than 1,500 users representing nearly every department at MIT. The Cryo-EM facility lives in the basement of the MIT.nano building and houses multiple electron microscopes and laboratory space for cryo-specimen preparation.

Thanks to her work at UC Berkeley, Sterling’s career trajectory has long been intertwined with the expanding use of cryo-EM in research. Sterling anticipated the need for experienced scientists to run core facilities in order to maintain the electron microscopes needed for cryo-EM, which range in cost from a staggering $1 million to $10 million each.

After completing her postdoc, Sterling worked at the Harvard University cryo-EM core facility for five years. When the director position for the MIT.nano Cryo-EM facility opened, she decided to apply.

“I like that the core facility at MIT was smaller and more frequently used by students,” Sterling says. “There’s a lot more teaching, which is a challenge sometimes, but it’s rewarding to impact someone’s career at such an early stage.”

A focus on users

When Sterling arrived at MIT, her first initiative was to meet directly with all the students in research labs that use the core facility to learn what would make using the facility a better experience. She also implemented clear and standard operating procedures for cryo-EM beginners.

“I think being consistent and available has really improved users’ experiences,” Sterling says.

The users themselves report that her initiatives have proven highly successful — and have helped them grow as scientists.

“Sterling cultivates an environment where I can freely ask questions about anything to support my learning,” says Bonnie Su, a frequent Cryo-EM facility user and graduate student from the Vos lab.

But Sterling does not want to stop there. Looking ahead, she hopes to expand the facility by acquiring an additional electron microscope to allow more users to utilize this powerful technology in their research. She also plans to build a more collaborative community of cryo-EM scientists at MIT with additional symposia and casual interactions such as coffee hours.

Under her management, cryo-EM research has flourished. In the last year, the Cryo-EM core facility has supported research resulting in 12 new publications across five different departments at MIT. The facility has also provided access to 16 industry and non-MIT academic entities. These studies have revealed important insights into various biological processes, from visualizing how large protein machinery reads our DNA to the protein aggregates found in neurodegenerative disorders.

If anyone wants to conduct cryo-EM experiments or learn more about the technique, Sterling encourages anyone in the MIT community to reach out.

“Come visit us!” she says. “We give lots of tours, and you can stop by to say hi anytime.”

The Skills Power Duo: Threat Intelligence and Reverse Engineering

The 2024 Summer Olympics may have garnered as much cybersecurity related media focus as the games themselves. Every two years, threat actors from a slew of countries seek notoriety by attempting to or succeeding in breaching one of the world’s largest sporting events, giving cybersecurity teams…

Igor Jablokov, CEO & Founder of Pryon – Interview Series

Igor Jablokov is the CEO and Founder of Pryon. Named an “Industry Luminary” by Speech Technology Magazine, he previously founded industry pioneer Yap, the world’s first high-accuracy, fully-automated cloud platform for voice recognition. After its products were deployed by dozens of enterprises, the company became Amazon’s…

Refining Intelligence: The Strategic Role of Fine-Tuning in Advancing LLaMA 3.1 and Orca 2

In today’s fast-paced Artificial Intelligence (AI) world, fine-tuning Large Language Models (LLMs) has become essential. This process goes beyond simply enhancing these models and customizing them to meet specific needs more precisely. As AI continues integrating into various industries, the ability to tailor these models for…

AlphaProteo: Google DeepMind unveils protein design system

Google DeepMind has unveiled an AI system called AlphaProteo that can design novel proteins that successfully bind to target molecules, potentially revolutionising drug design and disease research. AlphaProteo can generate new protein binders for diverse target proteins, including VEGF-A, which is associated with cancer and diabetes…

Atoms on the edge

Typically, electrons are free agents that can move through most metals in any direction. When they encounter an obstacle, the charged particles experience friction and scatter randomly like colliding billiard balls.

But in certain exotic materials, electrons can appear to flow with single-minded purpose. In these materials, electrons may become locked to the material’s edge and flow in one direction, like ants marching single-file along a blanket’s boundary. In this rare “edge state,” electrons can flow without friction, gliding effortlessly around obstacles as they stick to their perimeter-focused flow. Unlike in a superconductor, where all electrons in a material flow without resistance, the current carried by edge modes occurs only at a material’s boundary.

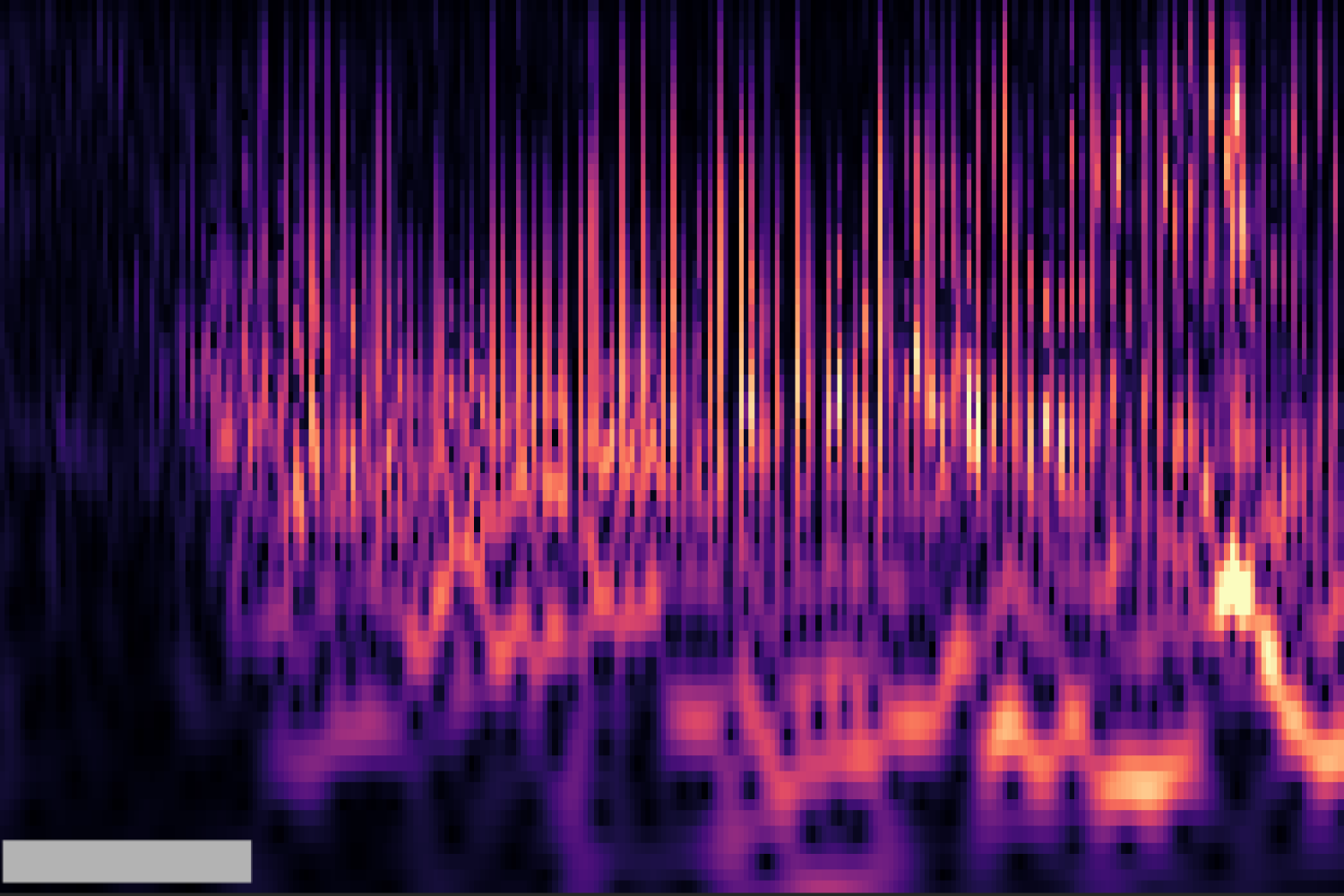

Now MIT physicists have directly observed edge states in a cloud of ultracold atoms. For the first time, the team has captured images of atoms flowing along a boundary without resistance, even as obstacles are placed in their path. The results, which appear today in Nature Physics, could help physicists manipulate electrons to flow without friction in materials that could enable super-efficient, lossless transmission of energy and data.

“You could imagine making little pieces of a suitable material and putting it inside future devices, so electrons could shuttle along the edges and between different parts of your circuit without any loss,” says study co-author Richard Fletcher, assistant professor of physics at MIT. “I would stress though that, for us, the beauty is seeing with your own eyes physics which is absolutely incredible but usually hidden away in materials and unable to be viewed directly.”

The study’s co-authors at MIT include graduate students Ruixiao Yao and Sungjae Chi, former graduate students Biswaroop Mukherjee PhD ’20 and Airlia Shaffer PhD ’23, along with Martin Zwierlein, the Thomas A. Frank Professor of Physics. The co-authors are all members of MIT’s Research Laboratory of Electronics and the MIT-Harvard Center for Ultracold Atoms.

Forever on the edge

Physicists first invoked the idea of edge states to explain a curious phenomenon, known today as the Quantum Hall effect, which scientists first observed in 1980, in experiments with layered materials, where electrons were confined to two dimensions. These experiments were performed in ultracold conditions, and under a magnetic field. When scientists tried to send a current through these materials, they observed that electrons did not flow straight through the material, but instead accumulated on one side, in precise quantum portions.

To try and explain this strange phenomenon, physicists came up with the idea that these Hall currents are carried by edge states. They proposed that, under a magnetic field, electrons in an applied current could be deflected to the edges of a material, where they would flow and accumulate in a way that might explain the initial observations.

“The way charge flows under a magnetic field suggests there must be edge modes,” Fletcher says. “But to actually see them is quite a special thing because these states occur over femtoseconds, and across fractions of a nanometer, which is incredibly difficult to capture.”

Rather than try and catch electrons in an edge state, Fletcher and his colleagues realized they might be able to recreate the same physics in a larger and more observable system. The team has been studying the behavior of ultracold atoms in a carefully designed setup that mimics the physics of electrons under a magnetic field.

“In our setup, the same physics occurs in atoms, but over milliseconds and microns,” Zwierlein explains. “That means that we can take images and watch the atoms crawl essentially forever along the edge of the system.”

A spinning world

In their new study, the team worked with a cloud of about 1 million sodium atoms, which they corralled in a laser-controlled trap, and cooled to nanokelvin temperatures. They then manipulated the trap to spin the atoms around, much like riders on an amusement park Gravitron.

“The trap is trying to pull the atoms inward, but there’s centrifugal force that tries to pull them outward,” Fletcher explains. “The two forces balance each other, so if you’re an atom, you think you’re living in a flat space, even though your world is spinning. There’s also a third force, the Coriolis effect, such that if they try to move in a line, they get deflected. So these massive atoms now behave as if they were electrons living in a magnetic field.”

Into this manufactured reality, the researchers then introduced an “edge,” in the form of a ring of laser light, which formed a circular wall around the spinning atoms. As the team took images of the system, they observed that when the atoms encountered the ring of light, they flowed along its edge, in just one direction.

“You can imagine these are like marbles that you’ve spun up really fast in a bowl, and they just keep going around and around the rim of the bowl,” Zwierlein offers. “There is no friction. There is no slowing down, and no atoms leaking or scattering into the rest of the system. There is just beautiful, coherent flow.”

“These atoms are flowing, free of friction, for hundreds of microns,” Fletcher adds. “To flow that long, without any scattering, is a type of physics you don’t normally see in ultracold atom systems.”

This effortless flow held up even when the researchers placed an obstacle in the atoms’ path, like a speed bump, in the form of a point of light, which they shone along the edge of the original laser ring. Even as they came upon this new obstacle, the atoms didn’t slow their flow or scatter away, but instead glided right past without feeling friction as they normally would.

“We intentionally send in this big, repulsive green blob, and the atoms should bounce off it,” Fletcher says. “But instead what you see is that they magically find their way around it, go back to the wall, and continue on their merry way.”

The team’s observations in atoms document the same behavior that has been predicted to occur in electrons. Their results show that the setup of atoms is a reliable stand-in for studying how electrons would behave in edge states.

“It’s a very clean realization of a very beautiful piece of physics, and we can directly demonstrate the importance and reality of this edge,” Fletcher says. “A natural direction is to now introduce more obstacles and interactions into the system, where things become more unclear as to what to expect.”

This research was supported, in part, by the National Science Foundation.