Josh Claman is the CEO of Accelsius, he is an expert global executive with over 30 years of experience in data center technology. He’s driven growth and innovation at NCR, AT&T, and, as a Dell Executive, he managed significant business units across Europe and the Americas, including as…

Anthropic to Google: Who’s winning against AI hallucinations?

Galileo, a leading developer of generative AI for enterprise applications, has released its latest Hallucination Index. The evaluation framework – which focuses on Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) – assessed 22 prominent Gen AI LLMs from major players including OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, and Meta. This year’s index…

The exponential expenses of AI development

Tech giants like Microsoft, Alphabet, and Meta are riding high on a wave of revenue from AI-driven cloud services, yet simultaneously drowning in the substantial costs of pushing AI’s boundaries. Recent financial reports paint a picture of a double-edged sword: on one side, impressive gains; on…

Amazon strives to outpace Nvidia with cheaper, faster AI chips

Amazon’s chip lab is churning out a constant stream of innovation in Austin, Texas. A new server design was put through its paces by a group of devoted engineers on July 26th. During a visit to the facility in Austin, Amazon executive Rami Sinno shed light…

5 Best AI Tools for Travel Planning (July 2024)

Artificial intelligence is improving the way we plan and experience travel. From personalized itinerary creation to language translation on the go, AI-powered tools are making trip planning more efficient and tailored to individual preferences. In this article, we’ll explore some of the best AI tools currently…

Copyleaks Review: A Better AI Content Detector than Turnitin?

Most people have heard of Turnitin, a plagiarism detection service widely used in academic institutions to check the originality of student work. It’s the industry standard, known for its reliability and accuracy. But what if there was an alternative as reliable with a more comprehensive suite…

How developers can use OpenAI’s SearchGPT

OpenAI is testing SearchGPT, a “temporary prototype of new AI search features that give you fast and timely answers with clear and relevant sources.” Keep reading as we cover everything you need to know about SearchGPT……

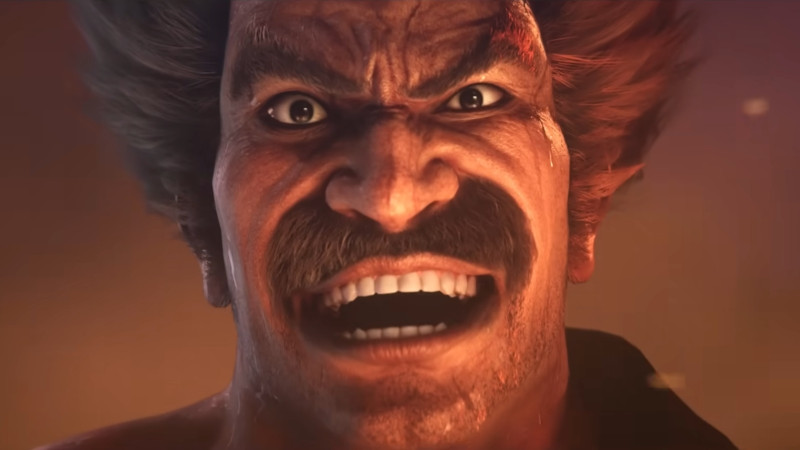

Heihachi Is Back And Comes To Tekken 8 This Fall

Tekken 8’s next Season 1 fighter was revealed during Evo this weekend, and it’s none other than Heihachi Mishima. The mainstay villain has apparently survived his presumed death (again) and is ready to reclaim his throne.

A cinematic trailer rolls out the red carpet for Heihachi, setting up his return after he was seemingly killed (i.e., tossed into a volcanic lava river) in Tekken 7. The video doesn’t explain how Heihachi managed not to melt into goop, but he does sport a Kazuya-esque scar on his chest now, so he didn’t walk away completely unscathed.

[embedded content]

Heihachi becomes available sometime this fall. He follows Eddy Gordo and Lidia Sobieska, who joined Tekken 8 in the spring (i.e., July 25) and summer, respectively, leaving one fighter left for the winter season. Owners of Tekken 8’s Deluxe, Ultimate, or Collector’s Editions automatically receive these fighters, and each can also be purchased individually for $7.99.

For more on Tekken 8, check out our review.

SNK Vs. Capcom: SVC Chaos Comes To PC, PS4, And Switch With New Features

Perhaps the most unexpected announcement at EVO 2024 was the reveal that 2003’s SNK vs. Capcom: SVC Chaos is being re-released. Not only does this make it available on modern platforms with new bells and whistles, but you can play it right now.

The game was originally launched in 2003 for the Neo Geo arcade before it was ported to PlayStation 2 (in Japan) and Xbox in the U.S. It pits 36 fighters from SNK franchises such as The King of Fighters, Samurai Shodown, and Metal Slug 2 against Capcom fighters from series like Street Fighter, Mega Man, Darkstalkers, and more.

[embedded content]

SVC Chaos now features quality-of-life updates such as a hitbox viewer, rollback netcode for online play, and an art gallery. It also makes formerly secret characters Athena and Red Arremer available from the start. The game’s surprise launch on Steam on July 20 followed its reveal, and it comes to PlayStation 4 and Switch today. You can pick it up now for $19.99.

Samurai Jack And Beetlejuice Are Headed To MultiVersus

MultiVersus has two new fighters on the way in the form of Jack from Cartoon Network/Adult Swim’s beloved animated series Samurai Jack and Beetlejuice of, well, Beetlejuice and its upcoming sequel (don’t make me write it a third time). The game is also getting a ranked mode.

Samurai Jack and Beetlejuice are part of the Season 2: Back in Time content, which kicks off tomorrow, July 23. Jack becomes available at launch, letting players cut down opponents using his signature katana (as you can see in the trailer below). Beetlejuice arrives later in the season at an unknown date, so we don’t get to see him in action just yet. However, Warner Bros. confirms he’ll become playable before the September 6 theatrical premiere of Beetlejuice Beetlejuice.

[embedded content]

Season 2 also introduces a new ranked mode, allowing players to battle for leaderboard points to earn exclusive rank-based cosmetics. A new map, the Warner Bros. Water Tower, will also be added.

MultiVersus is available now on PlayStation and Xbox consoles as well as PC. Since its return, the game has been bolstered by new fighters such as The Joker, The Matrix’s Agent Smith, and Friday the 13th’s Jason Voorhees.