76% of consumers in EMEA think AI will significantly impact the next five years, yet 47% question the value that AI will bring and 41% are worried about its applications. This is according to research from enterprise analytics AI firm Alteryx. Since the release of ChatGPT by…

Reading Beyond the Hype: Some Observations About OpenAI and Google’s Announcements

Google vs. OpenAI is shaping up as one of the biggest rivarly of the generative AI era….

Grand Theft Auto VI Targeting Fall 2025 Release Window

Grand Theft Auto VI’s reveal last December sent fans into a tizzy, but its then-distant 2025 release window immediately tempered that excitement. While the launch seemed more in reach now that we’re nearly midway through 2024, it appears we’ll have to wait another full year before playing it.

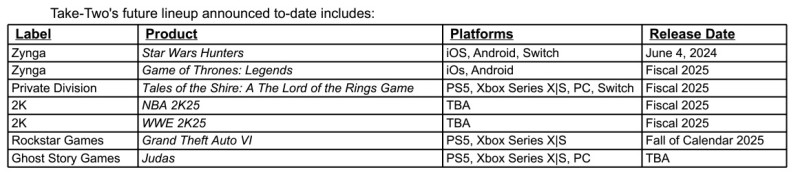

Publisher Take-Two released its 2024 year-end financial report today (thanks, PC Gamer), in which it states that Rockstar is targeting a Fall 2025 release window for GTA VI. This timing is reiterated in a calendar of the publisher’s upcoming releases, posted below.

Click to enlarge

Regarding GTA VI, Take-Two states, “We are highly confident that Rockstar Games will deliver an unparalleled entertainment experience, and our expectations for the commercial impact of the title continue to increase.” The game is slated to release for PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series X/S. A PC version has yet to be mentioned.

Grand Theft Auto VI takes players to a modern-day Vice City (the franchise’s parody of Miami, FL) and stars two protagonists, a female inmate named Lucia and her still-unnamed criminal male partner. To say anticipation is high would be an understatement; the premiere trailer garnered over 100 million views in only 24 hours, breaking a YouTube record.

As we continue the long wait for Grand Theft Auto VI’s launch, check out our video of Game Informer’s two resident Florida Men reacting to the debut trailer. You can also read about Take-Two’s recent closure of developers Roll7 (Rollerdrome, OlliOlli World) and Intercept Games (Kerbal Space Program 2).

Despite Speculation, Microsoft Will Reportedly Launch This Year’s Call Of Duty On Xbox Game Pass

Microsoft is reportedly planning to launch this year’s Call of Duty on its Xbox Game Pass subscription service, according to The Wall Stree Journal. This follows reports in previous weeks indicating Microsoft and Xbox were mulling over whether or not to launch the next iteration in the franchise on Game Pass, out of fear it might hurt sales.

After acquiring Activision Blizzard for a colossal $69 billion last year, fans and analysts have speculated about how Microsoft will handle the Call of Duty franchise moving forward. It will obviously be a big draw for Xbox Game Pass, pulling in new subscribers, but most every year, the new Call of Duty is the best-selling game of the year – save for last year, where Hogwarts Legacy took that crown – and a Game Pass launch could affect those sales numbers.

[embedded content]

However, this new report from The Wall Street Journal seemingly clears the air around that topic.

“Microsoft plans a major shake up of its video game sales strategy by releasing the coming installment of Call of Duty to its subscription service instead of the longtime, lucrative approach of only selling it a la carte,” the story reads.

Of course, things could change so we’ll see what happens. It’s likely we’ll be learning what the next Call of Duty game is next month as part of the gaming showcase summer that includes Summer Game Fest, Ubisoft Forward, and an Xbox Games Showcase followed by a secret direct that is probably focused on Call of Duty.

[Source: The Wall Street Journal]

What setting do you hope the next Call of Duty takes place in? Let us know in the comments below!

EA Sports College Football 25 Shows Off School Spirit In First Full Trailer And Screenshots

Yesterday, EA Sports College Football 25’s cover athletes and release date were revealed. Today, the game’s first full trailer provides the look at it in action.

The trailer shows that EA is seemingly going all out to replicate the pomp and passion of college football, with over-the-top team entrances, marching band performances, and mascots galore. It remains to be seen how fun or different the on-field action is compared to its Madden counterpart, but the game at least seems to capture the school spirit.

[embedded content]

EA also released a batch of new screenshots, which you can view in this gallery.

EA Sports College Football 25 launches on July 19 for PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series X/S. You can learn more about its various editions, pricing, and features here.

Fallout Is Coming To Fortnite

It’s a great time to be a Fallout fan, thanks to its excellent Amazon Prime series and the next-gen update for Fallout 4. But it seems like the fallout from this recent boom in popularity hasn’t died down quite yet. Thanks to a teaser shared on Fortnite’s official social media pages, we know that Fallout will be coming to Fortnite pretty soon

The teaser image shows power armor in a cloud of orange dust, accompanied by what appears to be some sort of industrial building. Other than that, there’s not much to go on, but we can make educated guesses. For one, Fortnite’s current season will end on May 24, so this is the perfect time to tease the skins that might be coming in the next battle pass. And if it’s anything like the recent Avatar: The Last Airbender and Star Wars crossovers, we might see Fallout-themed mechanics or areas appear on the battle royale map itself.

It will almost certainly involve some sort of cosmetic pack as well, which could include characters from the games, the Amazon Prime show, or both. Thanks to the teaser, we know power armor will be making an appearance, but it’s unclear whether it will be an item to equip in-game or a skin that can be unlocked or purchased.

For more Fortnite news, read about its recent crossover with Billie Eilish, its decision to allow players to block certain emotes, and its huge and mysterious collaboration with Disney.

What are you hoping to see included in this crossover? Let us know in the comments below!

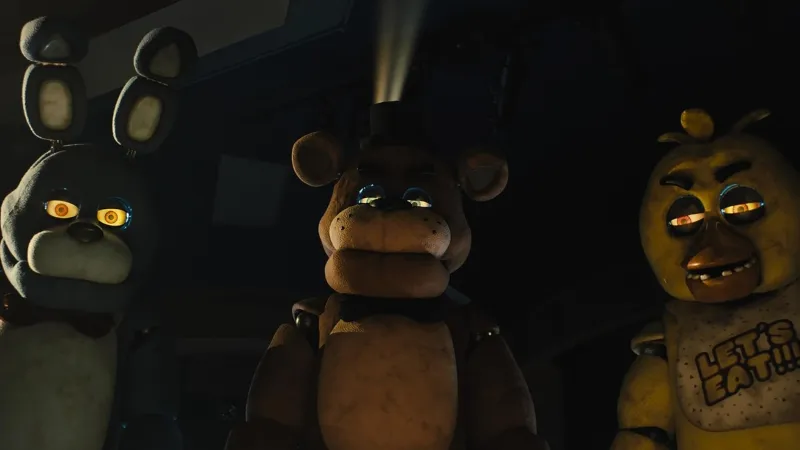

Five Nights At Freddy’s 2 Gets December 2025 Premiere Date

Five Nights At Freddy’s 2, the sequel to the 2023 film adaptation of the popular horror game, has a premiere date. Freddy Fazbear and friends will return to the big screen on December 5, 2025.

As reported by Variety, Blumhouse Productions announced the date alongside a slate of other upcoming films, including M3GAN 2.0 and The Black Phone 2. It’s not surprising to see Five Nights At Freddy’s getting a follow-up. It simultaneously premiered in theaters and on Peacock on October 27, 2023, and still managed to be a massive box office success. Grossing $297 million globally, it became the year’s highest-grossing horror film, Blumhouse’s highest-grossing film ever, and the most-watched movie on Peacock for five straight days.

The tagline for Five Nights At Freddy’s 2 reads, “Anyone can survive five nights. This time, there will be no second chances.” The sequel’s cast has not been announced, but the original starred Josh Hutchinson and included Matthew Lillard, Elizabeth Lail, Mary Stuart Masterson, and Piper Rubio. Director Emma Tammi is returning to direct the sequel, with FNAF creator Scott Cawthorn and Blumhouse founder Jason Blum once again assuming producer roles.

FNAF 2 won’t be the only video game film arriving in 2025. Mortal Kombat 2, the sequel to the 2021 reboot film, was recently confirmed to release in October of that year.

Unveiling the Control Panel: Key Parameters Shaping LLM Outputs

Large Language Models (LLMs) have emerged as a transformative force, significantly impacting industries like healthcare, finance, and legal services. For example, a recent study by McKinsey found that several businesses in the finance sector are leveraging LLMs to automate tasks and generate financial reports. Moreover, LLMs…

AI Chatbots Are Promising but Limited in Promoting Healthy Behavior Change

In recent years, the healthcare industry has witnessed a significant increase in the use of large language model-based chatbots, or generative conversational agents. These AI-powered tools have been employed for various purposes, including patient education, assessment, and management. As the popularity of these chatbots grows, researchers…

How AI turbocharges your threat hunting game – CyberTalk

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY:

Over 90 percent of organizations consider threat hunting a challenge. More specifically, seventy-one percent say that both prioritizing alerts to investigate and gathering enough data to evaluate a signal’s maliciousness can be quite difficult.

Threat hunting is necessary simply because no cyber security protections are always 100% effective. An active defense is needed, as opposed to dependence on ‘set it and forget it’ types of security tools.

But, despite active threat hunting, many persistent threats often remain undiscovered — until it’s too late. Or at least, that used to be the case.

Artificial intelligence is changing the game. Threat hunting is a task “…that could be accelerated, or in some cases replaced, by AI,” says Check Point’s CTO, Dr. Dorit Dor.

Evolve your threat hunting

Many threat hunters contend with visibility blind-spots, non-interoperable tools and growing complexity due to the nature of hybrid environments. But the right tools can empower threat hunters to contain threats quickly, minimizing the potential impact and expenses associated with an attack.

1. Self-learning. AI-powered cyber security solutions that assist with threat hunting can learn from new threats and update their internal knowledge bases. In our high-risk digital environments, this level of auto-adaptability is indispensable, as it keeps security staff ahead of attacks.

2. Speed and scale. AI-driven threat hunting engines can also process extensive quantities of data in real-time. This allows for pattern and indicator of compromise identification at speed and scale – as never seen before.

3. Predictive analytics. As AI-powered engines parse through your organization’s historical data, the AI can then predict potential threat vectors and vulnerabilities. In turn, security staff can proactively implement means of mitigating associated issues.

4. Collaborative threat hunting. AI-based tools can facilitate collaboration between security analysts by correlating data from different sources. They can then suggest potential threat connections that neither party would have observed independently. This can be huge.

5. Automated response. AI security solutions can automate responses to certain types of threats after they’re identified. For instance, AI can block certain IP addresses or isolate compromised systems, reducing friction and response times.

Implicit challenges

Although AI-based tools can serve as dependable allies for threat hunters, AI cannot yet replace human analysts. Human staff members ensure a nuanced understanding and contextualization of cyber threats.

The right solution

What should you look for when it comes to AI-powered threat hunting tools? Prioritize tools that deliver rich, contextualized insights. Ensure cross-correlation across endpoints, network, mobile, email and cloud in order to identify the most deceptive and sophisticated of cyber attacks. Make sure that your entire security estate is protected.

Are you ready to leverage the power of AI for threat hunting? Get ready to hunt smarter, faster and more efficiently while leveraging the power of AI. The future of threat hunting has arrived. Get more information here.

Lastly, to receive more timely cyber security news, insights and cutting-edge analyses, please sign up for the cybertalk.org newsletter.