Household robots are increasingly being taught to perform complex tasks through imitation learning, a process in which they are programmed to copy the motions demonstrated by a human. While robots have proven to be excellent mimics, they often struggle to adjust to disruptions or unexpected situations…

Enhance Your Production Quality with JVC’s KM-IP8/S4 Studio Switcher: – Videoguys

Dive into the features and benefits of JVC’s KM-IP8 S4 video mixer as Edgar Shane, GM of Engineering at GVC Professional Products, delves into its capabilities. From enhanced connectivity options to simplified production with VMix software, discover how this portable device is revolutionizing various markets, including houses of worship.

In the realm of video production, staying ahead requires the right tools. In a recent YouTube video from JVC titled “JVC’s KM-IP8/S4 Studio Switcher,” Edgar Shane, the esteemed General Manager of Engineering at GVC Professional Products, provides an insightful overview of the cutting-edge features packed into JVC’s KM-IP8 S4 video mixer.

At the heart of this innovative device lies the power of VMix software, seamlessly integrated to deliver a versatile performance. Supporting an array of video inputs, including 3G SDI and NDI, the KM-IP8 S4 opens doors to limitless creativity. Whether you’re orchestrating a live event or crafting engaging content, its multifaceted functions cater to diverse market needs.

Portability meets functionality with the KM-IP8S4 production system. Designed to adapt to various setups, from fly packs to portable rack mounts, its flexibility knows no bounds. This adaptability has earned accolades in specific applications such as houses of worship, where users have reported heightened audience engagement owing to the seamless production quality facilitated by VMix switching software.

Moreover, the KM-IP8 S4 doesn’t just stop at compatibility; it amplifies it. Seamlessly supporting JVC’s PTZ cameras, it opens doors to a realm of possibilities. With the advent of IP content, the device ushers in an era of streamlined connectivity, bidding adieu to cable clutter while enhancing accessibility.

But the innovation doesn’t end there. Edgar Shane sheds light on the cost-effective KM-IP8 model, a testament to JVC’s commitment to accessibility without compromising quality. Boasting features like NDI support and remote PTZ camera control, it’s a game-changer for those seeking efficiency without breaking the bank.

In conclusion, JVC’s KM-IP8/S4 Studio Switcher stands tall as a beacon of innovation in the realm of video production. With Edgar Shane’s expert insights, it’s evident that this powerhouse device isn’t just transforming workflows; it’s redefining possibilities. From enhanced connectivity to simplified control, it’s time to elevate your productions with JVC’s KM-IP8 series.

Watch the full video from JVC below:

[embedded content]

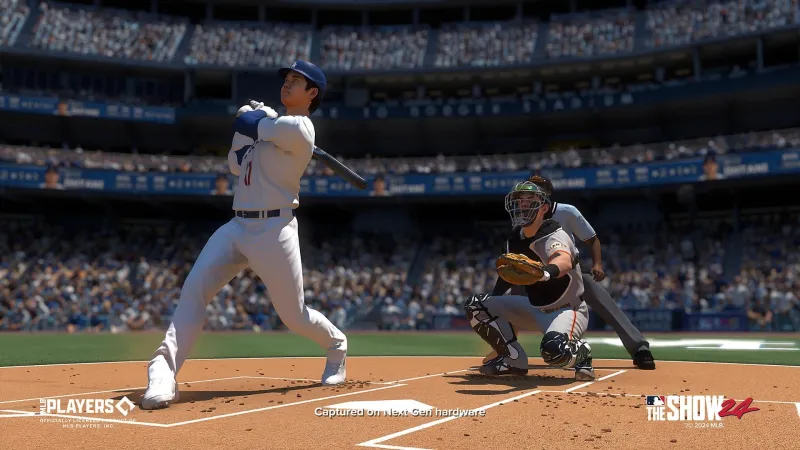

MLB The Show 24 Review – Breaking Barriers – Game Informer

MLB The Show’s commitment to nuance, iteration, and diversity is what sets it apart. Since the long-running series arrived on Xbox in 2021, the baseball sim has recontextualized sports games – emphasizing the purpose of communities while fitting in new features like Pinpoint Pitching, custom stadiums, and online ranked co-op. The Show 23 pushed the bar further with Storylines: The Negro Leagues, an interactive museum that detailed eight stars of baseball’s segregated past. This year’s iteration mirrors it with new Storyline episodes, a 60-minute tribute to Yankee legend Derek Jeter, and an original RTTS narrative where “Women Pave Their Way.” While it isn’t a hyper-creative leap forward, MLB The Show 24 finds a new swing by tethering style and strategy to baseball’s fundamentals.

MLB The Show 24’s gameplay is almost identical to The Show 23 – complete with 23’s quirks (Break Outlier, Pick Off Artist), throwing interfaces, swing feedback, and updates to attributes that associate the clutch attribute with RISP. There are 400 new animations in 24, plus logic improvements, new base sizes, and “Impact Plays” that add major league realism to defensive assists. However, it lacks an innovative change to a hitting and pitching engine we’ve seen in past entries. The new face and hair details are a sight to behold when Bryce Harper and Fernando Tatis Jr. are bat-flipping home runs next to cherry-kissed skies, but the immersion breaks when a star player drops a pop fly, misses routine grounders at third, or “soft tosses” a double play ball in extra innings. The Show 24’s updated lighting system provides a sharper, detailed look at the diamonds across Major League Baseball, and it takes advantage of a boost in exit velocities. This shift makes it easier to hit the ball in Petco Park, Chase Field, and Kauffman Stadium, all of which were problematic in past entries.

As expected, Storylines: Season Two is a delight. The docuseries, narrated by Negro Leagues Baseball Museum President Bob Kendrick, stands by the NLBM’s mission to “educate, enlighten, and inspire,” and it continues to combine archival footage, gameplay-driven scenarios, and personal anecdotes to illustrate why baseball is the most romanticized sport on Earth. The new season introduces 10 new Negro League heroes, with four episodes available at launch – reducing the initial runtime to institute a more immersive environment for Kendrick’s narrations.

[embedded content]

And it doesn’t miss. Season Two embraces the Negro Leagues’ revered architects, highlighting how the introduction of “night baseball” in the 1930s led to the discovery of a phenom known as Josh “The Black Babe Ruth” Gibson. It recalls how Walter “Buck” Leonard was a thinking man’s player and a fixture for Pittsburgh’s Homestead Greys; how Henry “The Hammer” Aaron started his career with the 1952 Indianapolis Clowns as a “skinny, cross-handed hitting” shortstop; and how Toni “The Trailblazer” Stone learned how to play with the fellas before becoming the first of three pioneering women to play professional ball. All four narratives are accompanied by iconic moments – such as recreating Stone’s single against the immortal Satchel Paige and hitting a home run with Aaron and the Milwaukee Braves in Sportsman’s Park – and it never once feels overly dramatized. Instead, every photograph, audio excerpt, and subtle ode to Pennsylvania’s Greenlee Field and Newark’s Ruppert Stadium is an organic lesson in American history. Bold and full of soul thanks to scores by Stevie Wonder, Marlena Shaw, and A Tribe Called Quest.

That attention to detail is also embedded in Storylines: Derek Jeter – a ‘90s-based spinoff mode that pays homage to “The Captain” and his New York Yankees-inflected path to baseball nobility. Much like Season Two, it’s a collection of career-defining, playable moments from 1995 to 2000, including his first career hit versus the Mariners in Seattle’s Kingdome, his famous “jump throw” from Game 1 of the 1998 American League Championship, and how the Yankees’ initial All-Star Game MVP drove the club past the New York Mets to seal a three-peat in the 2000 World Series. It’s not the most compelling narrative, particularly if you’re a fan of the Yankees’ rivals, but thanks to San Diego Studio’s Live Content team, it does offer a surplus of in-game rewards, including Atlanta’s 2000 All-Star Game uniforms and Subway Series player items for Diamond Dynasty.

There’s also an interactive subway map, complete with graffiti, billboards, and “New York-isms”, that provides a snapshot of the city and a fan base with high expectations, but it’s difficult not to imagine Storylines being a distinctive voice for pockets of culture that are less commercialized.

Other modes like Franchise and March To October have been largely untouched – pairing The Show 23’s amateur scouting system, postseason formats, and “Ohtani Rule” with custom game conditions and Prospect Promotion Incentive (PPI). Road To The Show is directly tied to the Draft Combine, a four-day event where hitting, pitching, and fielding is graded to provide an accurate projection for attributes, comparisons, and club interest for the MLB Draft. It provides explanations for multiple ballplayer archetypes and their position’s focus, but the core narrative lacks creative ingenuity that goes beyond dated minigames and dialogue systems. Especially when it reaffirms what the community already knows: RTTS is for ‘80s mullets and XP bugs.

“Women Pave Their Way” is a fresh addition that alters the Road To The Show formula in new and exciting ways because it presents an atypical narrative about breaking barriers in baseball. It’s a unique pivot, led by narrative designer Mollie Braley and USA Baseball’s Kelsie Whitmore, and it’s one that promotes awareness of the women who play baseball and that other aspiring athletes are capable of competing at multiple levels. It sounds like “marketing jazz,” but Braley and SDS use pre-recorded video content with MLB Network’s Robert Flores, Lauren Shehadi, Dan O’Dowd, Melanie Newman, and Carlos Peña to stress the physical and mental adversity that is attached to carving a path in minor-league systems. They don’t sugarcoat anxieties or rewrite old baseball traditions; their intention is to inspire new and returning players to chase their lifelong dreams, and it’s a vision that gets its own full circle moment when MLB.com’s Sarah Langs starts detailing RPMs and spin rates.

With the exit velocities, Diamond Dynasty is off to its best start in years. The Show 24 alters 23’s Ultimate Team concepts to reintroduce “Seasons 2.0” – an expansion on “Sets & Seasons” that ditches 99 OVR player items on Day One for a traditional power creep, multiple Wild Card slots, monthly Team Affinity drops, and reward paths that differentiate Ranked, Events, and Conquest. There are Cornerstone Captains that implement seasonal archetypes for team building and new Team Captains that add comparable boosts to hitting and pitching attributes for all 30 MLB clubs – solely to create hypotheticals like Yankees vs Dodgers, Cubs vs Phillies, and Rays vs Padres. There are still microtransactions, sure, but The Show’s monetization policies are less iniquitous than Madden NFL, FIFA, and NBA 2K’s practices because they rarely “gatekeep” limited drops when there are hundreds of diamond player items “sitting at home.” Diamond Dynasty is still in need of a visual overhaul, a Custom Practice mode, a new uniform creation system, and more unique customization options that tap into collaborations with Sanford Greene, King Saladeen, and Takashi Okazaki, but listening to a community’s input is a start – especially if it continues.

MLB The Show 24 doesn’t hit it out of the park at every at-bat, but it doesn’t have to. The series is in the middle of an experimental phase that’s trying to mitigate its perpetual “online vs. offline” war. Despite a clear lack of innovation in mechanics, it has still found a way to impress, inspire, and engage with a younger generation that shares an interest in history. The Show’s art team is second to none, its OST shuffles Eladio Carrion, IDLES, Flowdan, and Brittany Howard with the grace of a 2 Chainz verse, and its “Grind 99” mantra has been edited to be a modern ideology – “play however and whenever.” It’s why Diamond Dynasty is the best take on Ultimate Team in terms of approachability and competition and why The Show 24 hopes to reignite annual titles through personalization. As the great Toni Stone once implied: “Get you one ‘cause I got mine.”

Transforming Wildlife Photography Workflow: A Collaboration with Atomo – Videoguys

Discover how award-winning photographer and videographer, Mia Stawinski, revolutionized her wildlife photography workflow using Atomos Ninja Ultra monitor and Sony Ci Media Cloud, capturing the essence of nature effortlessly.

In a captivating journey through the wilderness of Botswana, award-winning photographer and videographer, Mia Stawinski, showcases the seamless integration of Atomos Ninja Ultra monitor and Sony Ci Media Cloud in her latest project. With a focus on preserving the raw beauty of nature and wildlife, Mia unveils how this ultimate pairing transformed her workflow, elevating her craft to new heights.

Unlocking the full potential of her Sony A7R V mirrorless camera, the Atomos Ninja Ultra monitor empowered Mia to record in ProRes RAW, simplifying her setup and allowing for uninterrupted focus on capturing breathtaking moments. By harnessing the power of ProRes, Mia preserved every intricate detail, vibrant hue, and dynamic range in her footage, ensuring a true-to-life representation of the wild.

Equipped with essential monitoring tools such as focus peaking, zoom, and vectorscope, Mia seamlessly reviewed her footage, all while maintaining a discreet presence to avoid disturbing the natural habitat of her subjects. This newfound efficiency afforded her more time behind the camera, enriching her storytelling with every frame captured.

With the seamless integration of Sony Ci Media Cloud, Mia transcended the constraints of traditional file management, securely storing and accessing her footage from anywhere in the world. Collaborating with clients became a breeze as they provided real-time feedback through the intuitive platform, resulting in a final product that surpassed expectations.

Gone are the days of cumbersome file transfers and reliance solely on internal recording capabilities. With Atomos Ninja Ultra and Sony Ci Media Cloud, Mia’s workflow has undergone a revolutionary evolution, allowing her to focus on what she does best – immortalizing the untamed beauty of the natural world.

Watch the full video from Atomos below:

[embedded content]

Signs You Have Overstaffed Your Small Business – Technology Org

Managing a small business is daunting, and especially when you are wasting resources at places where you could…

Exciting time Ahead for the iGaming Industry – Technology Org

Online gaming has seen many changes in the past decade. It’s an industry that gives a very blank…

Marvel Rivals Is A Team-Based Hero Shooter From NetEase Games

The Marvel Universe is expansive and chockful of some of pop culture’s greatest heroes. NetEase Games is taking the word “hero” literally and placing the characters from Marvel in a free-to-play 6v6 hero shooter. Marvel Rivals promises to bring the most popular and iconic superheroes and supervillains to the arena with destructible environments, unique Team-Up skills, and more.

Marvel Rivals offers 6v6 PVP action featuring arenas from across the Marvel Multiverse, including Asgard and Tokyo 2099. The title touts a deep roster of heroes and villains to choose from, including members of the Avengers, Guardians of the Galaxy, X-Men, and more, all with unique Team-Up skills that play off various synergies between heroes. The closed alpha in May will feature more than a dozen characters, while the announce trailer (below) features 18 characters that represent the current roster.

[embedded content]

If your favorite Marvel hero or villain isn’t on that initial roster, NetEase promises a “robust” post-launch roadmap. According to the company, each seasonal drop will introduce new playable characters and maps. “Marvel Rivals is one of our most ambitious development projects,” Haluk Mentes, head of Marvel Games, said in a press release. “Since the conceptualization of the game and throughout our collaboration, our Marvel team has poured our hearts and souls into this project, and we are thrilled to work with the incredible team at NetEase Games to help deliver the ultimate Super Hero team-based PVP shooter.”

The story of Marvel Rivals features Doctor Doom and his 2099 counterpart forcing universes to collide in the Timestream Entanglement, creating new worlds. Superheroes and supervillains from the multiverse must band together and fight other groups of multiversal characters to defeat the two Dooms and save the multiverse.

NetEase Games touts its team members who worked on franchises like Battlefield and Call of Duty as being instrumental in the development of Marvel Rivals, but the studio operates with a global team of developers. Marvel Rivals is currently in development for PC, with a closed alpha kicking off in May. To sign up for the upcoming tests, you can visit MarvelRivals.com.

Unveiling HuddleCamHD SimplTrack 3: Intro & Demo | Your 2024 Tracking – Videoguys

On This Videoguys Live, James introduces the HuddleCamHD SimplTrack3. Discover the latest innovation in camera technology, perfect for classrooms or corporate boardrooms. Enhance your video conferencing and live streaming experience with precision tracking that’s ahead of its time.

[embedded content]

|

HuddleCamHD SimplTrack3 20X Optical Zoom

|

What is Auto-Tracking?

- Automated Movement: PTZ cameras can pan, tilt, and zoom automatically to follow movement.

- Intelligent Tracking: Used to detect and follow subjects within the camera’s view.

- Hands-Free Operation: Reduces the need for manual camera adjustments, providing ease of use during events.

- Wide Coverage: Capable of covering a large area without the need for multiple fixed cameras.

- User-Friendly Interface: Allows for easy setup of tracking parameters and zones.

The Tracking Zone encompasses the entire area where an auto-tracking subject might move across your frame. It’s designed to ensure smooth tracking of the presenter or lecturer, covering a wide range and offering flexibility in movement.

The Preset Zone represents an innovative feature where an automated preset is triggered when the camera enters a selected area. This could include switching to a separate camera, activating a stage light, or any other preset tailored to enhance the presentation or lecture experience. The SimplTrack3 contains 8 preset zones.

How does it help in the Corporate Boardroom?

- Streamlined Meetings: Automatically follows speakers, hands-free operation, and uninterrupted presentations.

- Cost-Effective: No need for multiple cameras or camera operators, lowering overall costs.

- Professional Quality: Ensures high-quality video for live streams or recordings.

- Increased Engagement: Keeps remote participants engaged by focusing on active speakers and relevant content.

- Flexibility: Offers the ability to cover the entire room without manual intervention.

- Easy Integration: Compatible with most video conferencing platforms, facilitating seamless communication.

How does it help in the Classroom?

- Engagement: Keeps students engaged by focusing on the instructor or demonstration.

- Accessibility: Allows remote students to feel as if they’re in the classroom by providing a clear view of the instructor and teaching materials.

- Efficiency: Having no camera operators enables educators to focus on teaching without worrying about camera adjustments.

- Flexibility: Adapts to different teaching styles and classroom layouts.

- Inclusivity: Supports diverse learning environments to aid students.

- Convenience: Simplifies the recording of lectures for later review, benefiting students who missed class or wish to revisit the material.

Why is the Dual Camera Sensor better?

- Advanced Auto-Tracking: Dual sensors ensures that every important moment is captured with high-definition clarity.

- Enhanced Precision: Captures both wide-angle and close-up views, which enhances the camera’s ability to maintain focus on the subject while ignoring irrelevant movements.

- Improved Performance: Adapts to changes in height and position of the subject, which is particularly useful in educational and stage production settings.

- Smart Framing: The camera can seamlessly transition between tracking an individual presenter and framing a group, ideal for dynamic interactions in classrooms and conferences.

- Flexibility and Scalability: The system supports multiple video outputs and dedicated management software, allows easy integration and scalability.